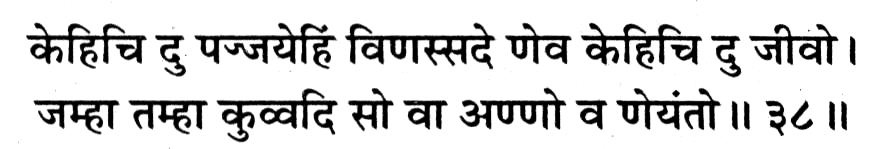

kehici du pajjayehiṃ viṇassade ṇeva kehici du jῑvo.

jamhā tamhā kuvvadi so vā aṇṇo va ṇeyaṃto..38

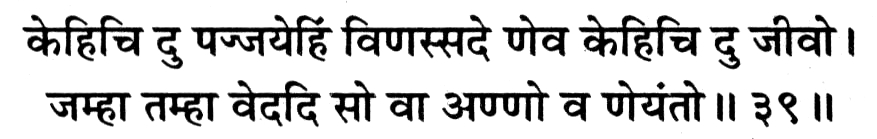

kehici du pajjayehiṃ viṇassade ṇeva kehici du jῑvo.

jamhā tamhā vedadi so vā aṇṇo va ṇeyaṃto..39

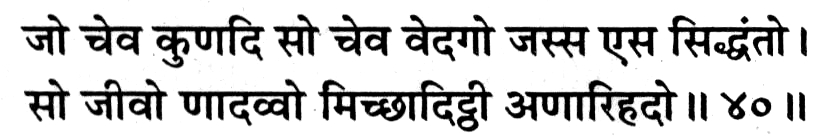

jo ceva kuṇadi so ceva vedago jassa esa siddhaṃto.

so jῑvo ṇādavvo micchādiṭṭhῑ aṇārihado..40

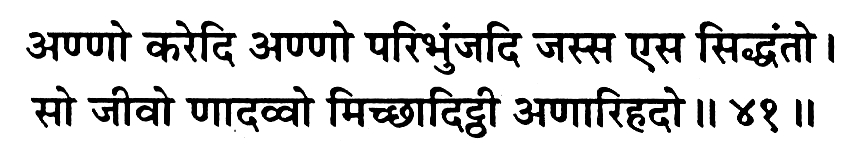

aṇṇo karedi aṇṇo paribhuṃjadi jassa esa siddhaṃto

so jῑvo ṇādavvo micchāditthῑ aṇārihado..41

(Jamhā) [Since] (jῑvo kehici du pajjayehi viṇassade kehici du ṇeva) the soul ceases to exist from one aspect [change/ modification/paryāyārthika naya] but continues to exist—is eternal from another aspect [persistence/dravyārthika naya); (tamhā) therefore, [persistence—through—modes being the nature of soul] (so vā kuvvadi va aṇṇo ṇeyaṃto) it invalidates the [absolutist] view that the soul, that enjoys the fruit, is [absolutely] identical to the one who acts or [absolutely] different from it.

(Jamhā) [Since] (jῑvo kehici du pajjayehiṃ viṇassade kehici du ṇeva) the soul ceases to exist from one aspect, but continues to exist from the other; (tamhā) therefore [persistence—through—modes being the nature of the soul], (so vā vedadi va aṇṇo ṇeyaṃto) it invalidates the [absolutist] view that the soul, that acts, is [absolutely] identical to the one who enjoys the fruit or [absolutely] different from it.

(Jo ceva kuṇadi so ceva vedago jasa esa siddhaṃto) Anyone, who believes that the soul that acts is absolutely identical with the soul that enjoys [the fruits thereof], (so jῑvo micchādiṭṭhῑ aṇārihado ṇādavvo) shoud be known as one who is not a true believer of Jain (Ārhata) faith, as his faith is perverted.

(Aṇṇo karedi aṇṇo paribhuṃjadi jassa esa siddhaṃto) Anyone who believes that the soul that acts is absolutely different from the soul that enjoys [the fruit thereof] (so jῑvo micchādiṭṭhῑ aṇārihado ṇādavvo) shoud be known as one who is not a the believer of Jain (Ārhata) faith, as his faith is perverted.

Annotations:

In the preceding verses, we saw how the author refuted the absolutist doctrines of Sāṃkhya system. In the above verses, he takes up another absolutist system—the Buddhists—for refutation.

As we have observed repeatedly, the Jain doctrine of non-absolutism has been elaborated and systematized on the basis of experience, and if there appears to be any snag in it, it is due to that in the very nature of things. The Jain approach to the supreme problem is co-ordination of experience and reason. Logic must cooperate with experience in its quest for the knowledge of ultimate reality. The Jains believe that all absolutistic conceptions are vitiated by some defect or other and they all go against the verdict of experience. The absolutists, however, dismiss the verdicts of experience as untrustworthy and dismiss them as imagination born of nescience.

The Buddhists have denied a permanent self underlying the course of psychical events and replaced it by a series, supposed to be governed by the law of causality, in which the previous conscious unit is defunct when the succeeding unit appears. In the Buddhist theory the cause ceases to be when the new effect comes into being. This makes the continuity of the personal life impossible and accordingly the necessity of the law of karma that the performer of good or evil act will have to bear the consequence—all these become impossible, unless one accepts both staticity and change in the selfsame entity—the soul—with reference of identical space and time.

In these verses, the author reiterates the basic non-absolutist doctrine and uses it to refute the absolutist's views. In the preceding verse, he had refuted the absolute permanence—immutability of the conscious principle as propounded by Sāṃkhya and others. Here he refutes the absolute impermanence and substancelessness held by the Buddhists.

We have already seen that the Jain position is quite distinct from that of the absolutist's and does not endorse either eternalism or nihilism. The Jain conception of permanence is not absolute staticity but persistent flow, i.e., the substance persists through modes. It 'is' as well as 'becomes'. Just as dead staticity is incompatible with change, absolute being is inconsistent with becoming. But becoming, according to Jains, is not a derivative of being but its necessary concomitant and hence being and becoming are not mutually incompatible. The question "Why should a thing become and change?" is as absurd as the question "Why should a thing exist?" The thinker who presume Being as absolutely static and conceive Becoming as a derivative of being are landed in self-contradiction. They eventually reject either being or becoming or both as illusory.

With these doctrines, the Jains hold the soul to be an eternal entity persisting through different births and bodies. They believe in good and bad actions and also their fruits. But the Buddhists do not believe in a spiritual substance persisting through various births, according to them the soul that acts is absolutely different from the one that enjoys the fruits of the actions. Thus, concluded the author, all absolutist philosophies carry perverted beliefs and are therefore non-believers.

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar