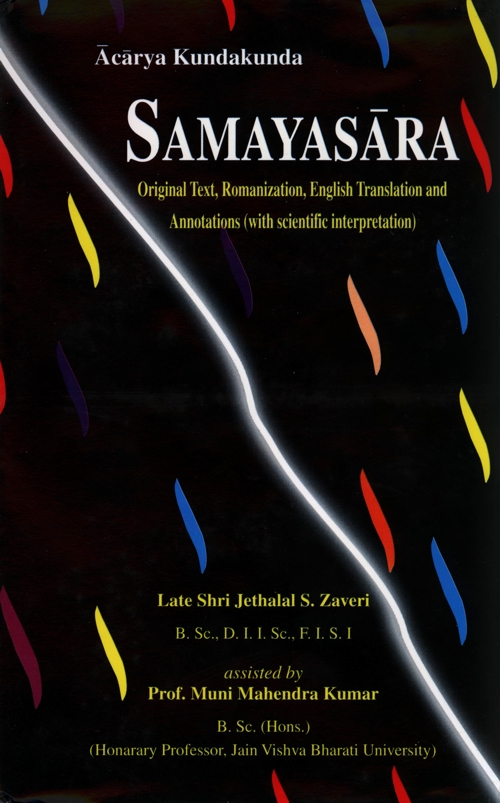

evaṃ saṃkhuvadesaṃ je du parūviṃti erisaṃ samaṇā.

tesiṃ payaḍῑ kuvvadi appā ya akāragā savve..33

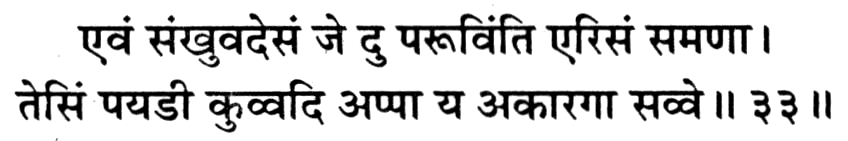

ahavā maṇṇasi majjhaṃ appā appāṇamappaṇo kuṇadi.

eso micchasahāvo tumhaṃ evaṃ bhaṇaṃtassa..34

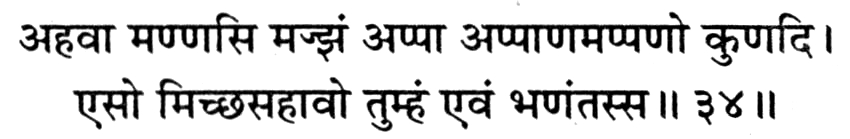

appā ṇiccāsaṃkhejjapadeso desido du samayamhi.

ṇa vi so sakkadi tatto hῑṇo ahiyo va kāduṃ je..35

jῑvassa jῑvarūvaṃ vittharado jāṇa logamittaṃ hi.

tatto so kiṃ hῑṇo ahiyo ya kadaṃ bhaṇasi davvaṃ..36

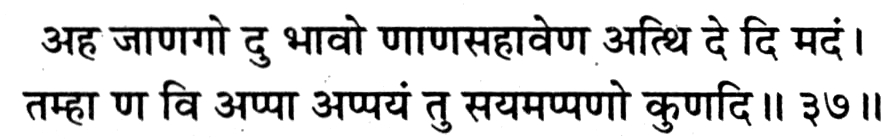

aha jāṇago du bhāvo ṇāṇasahāveṇa atthi de di madaṃ.

tamhā ṇa vi appā appayaṃ tu sayamappaṇo kuṇadi..37

[Presenting the above false preaching by Sāṃkhya system as given in the preceding verses, the author says] (Evaṃ du erisaṃ saṃkhuvadesaṃ je samaṇā paruviṃi) In this way, some pseudo-ascetics [śramaṇābhāsa] preach and propagate the false beliefs held by the Sāṃkhya system, (tesiṃ payaḍi kuvvadi) according to which [it is proved that] prakṛti (the physical substance) is the only active agent (ya) and (savve appā akāragā) all the souls (conscious entities) are inactive/non-doers (akartā).

(Ahavā) Or alternatively (maṇṇasi ‘majjhaṃ appā appaṇo appāṇaṃ kuṇadi’) [if] you [state and] maintain [that] 'my soul transforms itself by itself and produces the conscious substance', (evaṃ bhaṇattassa tumhaṃ eso micchasahāvo) then also, [you] making such statement, your belief becomes perverted.

[Refuting the above belief of Sāṃkhya, the author continues—[Since] (samyamhi du appā ṇiccā saṃkhejjapadeso desidi) according to the [original and true] scriptures, the soul is an [uncreated] eternal substance, having innumerable soul-units (pradeśas.)[1] (Je so tutto hῑṇo ya ahiyo kāduṃ ṇa vi sakkadi) Not a single pradeśa of the soul, can be reduced or added (either by itself or by anything else).

(Vittharado jῑvassa jῑvarūpaṃ logamittaṃ jāṇa) Know that, spatially, each soul [which is numerically different], when fully extended, is precisely co-extensive with entire Loka [cosmos]. (Tutto so kiṃ hῑṇo ahiyo ya?) Can that soul be made smaller or bigger than that [quantity]? (Bhanasi davvaṃ kadaṃ) [Therefore] your [above] statement that the substance soul has transformed itself [is unjustifiable].

(Aha jāṇago du bhāvo ṇāṇasahāveṇa atthi de di madaṃ) And again if you believe and accept that consciousness remains of the nature of knowledge, (tamhā appā sayaṃ appaṇo appuyaṃ tu ṇa kuṇadi) then it is proved that the soul cannot change itself by itself (of its own accord).

Annotations:

Amongst the absolutist philosophies, Sāṃkhya School appears to be closest to Jains and it seems that, about the time of Ācārya Kundakunda, some Jain thinkers and even ascetics must have had leanings towards Sāṃkhya views. Such ascetics were called pseudo-ascetics (śramaṇahhāsa) or the Jain heretics.

We shall, very briefly, review the Sāṃkhya doctrine. Sāṃkhya School recognizes two primordial categories, viz., puruṣa (self) and prakṛti (non-self). The former is the principle of consciousness which witnesses the world process of which prakṛti is the ground. Puruṣa is an absolutely unchanging (immutable) permanent entity. All change and all activity emanate from prakṛti. Various changes, both physical and psychical, are due to prakṛti alone. Though puruṣa is not responsible for any activity, good or evil, he enjoys the fruits of the actions of prakṛti. The school does not attempt at defining the relation between these two; somehow puruṣa appears to have become one with prakṛti and to enjoy it. Everything, good or bad, belongs to the prakṛti, and the puruṣa is there only as an indifferent onlooker. Also, it does not define the function of the puruṣa in the attainment of final enlightenment. Puruṣa is inactive consciousness intelligizing the prakṛti. Final enlightenment is a state of the prakṛti comprehending the truth of the separate identity of puruṣa from itself. Although the puruṣa is of the nature of consciousness, the functions of knowing, thinking and willing do not belong to him.

The pseudo-ascetics tried to equate karmic matter with the prakṛti and held that karma was responsible for every change and activity, physical or psychical, and the soul itself, being absolutely inactive and immutable, was not responsible for the evils of the world. The true Jains, naturally, could not accept the propriety of such a position. If the soul is involved in the evils, the evil must belong to it. Moreover, the conception of evil loses all its meaning and purpose unless the soul is really associated with it. If the soul is merely a spectator/witness, absolutely uninfluenced by the action of karma he must remain forever in a liberated/emancipated state and there would be no worldly state of existence—saṃsāra. Hence the conclusions derived from the Sāṃkhya doctrine are contradicted by actual experience and are, therefore, unbelievable absurd. The Sāṃkhya system tries to preserve the immutable character of the puruṣa by keeping him free from all functions whatsoever. But we can see that it did so at the cost of becoming self-contradictory. Ācārya Hemacandra sums up some of the self-contradictions as under: Consciousness does not know the objects, the buddhi is unconscious. Bondage and emancipation do not belong to the puruṣa. And what else self-contradictory has not been composed by the Sāṃkhyas. How can consciousness be without knowledge and the knowing buddhi without consciousness? How can the puruṣa enjoy the prakṛti if he is absolutely immutable?

In particular, Sāṃkhya system fails to give any explanation for the empirical state of existence.

Contrarily, the Jain doctrine of non-absolutism, convincingly, provide the explanation for the worldly state by establishing concrete relation between the soul and the karma. While it is accepted by the Jains that the karmic matter is undoubtedly the main operative principle responsible for all changes/physical and psychical—in the worldly state of existence of a person, the soul itself does not remain absolutely aloof and inactive witness. There is a positive response on the part of the soul. The interaction and the consequent psycho-physical changes are due to the responsive attitude of the soul. The karmic matter by itself, is totally impotent to produce any psychical change in the absence of the soul's responsive reaction. We have already, dealt with psycho-physical relations in chapter III. Suffice it to say here that the psychical changes are brought about by the responsive attitude of the soul and the interaction of the soul and the karmic matter. It should be remembered that modification/change in the conscious substance cannot be brought about by the karmic matter alone. In the case of rise or fruition of karma, the stimulation is initiated by the physical substance and in the case of subsidence and dissociation, it is the conscious substance that initiates the change and the karmic matter responds. Thus, both—the soul as well as the karma—are active and mutable.

Hence, the worldly state of the soul—the empirical ego—must be regarded as an active causal agent capable of producing its own modification in response to the changes in the states and processes of the karma. Thus, according to Jains, the empirical soul is both active and mutable, i.e., amenable to change. This, of course, is the situation in the worldly state of existence and the empirical aspect (vyavahāra naya). The position is totally different when the soul acquires discriminative wisdom and becomes aware of his pure nature and is able to separate it from the non-self. It, then takes the ultimate or the transcendental view of the situation and becomes an inactive spectator/witness much the same as the Sāṃkhya puruṣa.

What then is the difference between the two schools of thought? It is clear from the above discussion that the absolutist Sāṃkhya, who regard the principle of consciousness—paruṣa as absolutely immutable and are not prepared to admit any change in its being, fail to account for the reality of the worldly existence. Since there is no bondage, there cannot be any liberation. Is there any justification or need for earnest striving for the release of the prakṛti which, after all, is only an unconscious instrument of fulfillment of the interests of the puruṣa? On the other hand, the non-absolutist Jains admit the reality of the worldly existence and regard it as a state of bondage and degradation of the soul, which according to them is eternal but not absolutely unchanging. They combine both empirical and transcendental aspects, and accept the change/mutation of the soul as real. The author is perfectly justified in refuting the Sāṃkhya system because of its failure to explain the nature of concrete reality of the worldly existence.

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar