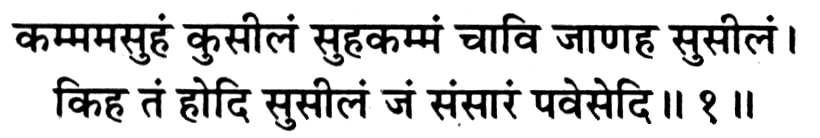

kammamasuhaṃ kusῑlaṃ suhakammaṃ cāvi jāṇaha susῑlaṃ.

kaha taṃ hodi susῑlaṃ jaṃ saṃsāraṃ pavesedi..1

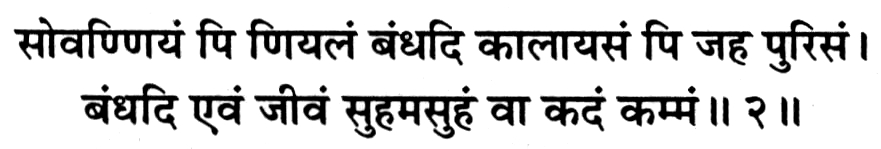

sovaṇṇiyaṃ pi ṇiyalaṃ baṃdhadi kālāyasaṃ pi jaha purisaṃ.

baṃdhadi evaṃ jῑvaṃ suhamasuhaṃ vā kadaṃ kammaṃ..2

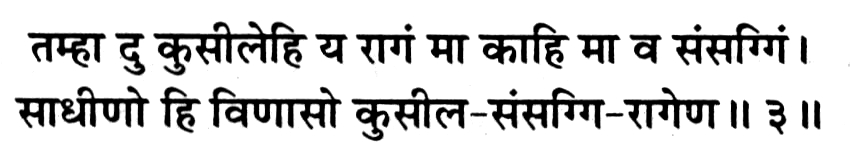

tamhā du kusῑlehi ya rāgaṃ mā kāhi mā va saṃsaggiṃ.

sādhῑṇo hi viṇāso kusῑla-saṃsaggi-rāgeṇa..3

jalia ṇāma ko vi puriso kucchiyasῑlaṃ jaṇaṃ viyāṇittā.

vajjedi teṇa samayaṃ saṃsaggiṃ rāgakaraṇaṃ ya..4

emeva kammapayaḍῑ sῑlasahāvaṃ hi kucchidaṃ ṇāduṃ.

vajjaṃti pariharaṃti ya taṃ saṃsaggiṃ sahāvaradā..5

ratto baṃdhadi kammaṃ muñcadi jῑvo virāgasaṃpaṇṇo.

eso jiṇovadeso tamhā kammesu mā rajja..6

(Asuhaṃ kammaṃ kusῑlaṃ avi ca suhakammaṃ susῑlaṃ jāṇaha) It is commonly believed that the fruition of auspicious karma is virtuous/desirable while that of inauspicious ones is vicious/undesirable; but (jaṃ saṃsāraṃ pavesedi taṃ kiha susῑlaṃ hodi) how can that which continues the cycles of births and deaths [the worldly state of existence] be considered virtuous/desirable?

(Jaha sovaṇṇiyaṃ ṇiyalaṃ pi kālāyasaṃ pi purisaṃ baṃdhadi) Just as fetters made from gold binds a person as efficiently as those made from iron, (evaṃ suhamasuhaṃ vā kadaṃ kammaṃ jῑvaṃ baṃdhadi) in the same way karma, whether it is auspicious or inauspicious, binds the soul [fetters it to the wheel of worldly state].

(Tamhā du) That is why (kusilehi ya rāgaṃ mā kāhi) never form an attachment for these [auspicious as well as inauspicious] vicious karma, (va saṃsaggiṃ mā) nor form a close association with them (hi) because (kusῑlasaṃsaggi rāgeṇa) close association with what is evil (sādhῑṇo viṇāso) [positively] results in destruction of natural bliss.

(Jaha nāma ko vipuriso kucchiyasῑlaṃ jaṇaṃ viyāṇittā) Just as a person, as soon as he becomes aware of the evil nature of someone, [his associate] (teṇa samayaṃ saṃsaggiṃ rāgakaraṇaṃ ca vajjedi) immediately terminates association and attachment for this person; (emeva) in the same way (sahāvaradā) the soul, who is desirous of natural bliss [from his own SELF], (kammapayaḍῑ sῑlasahāvaṃ kucchidaṃ ṇāduṃ) recognizes the evilness of all karma [even that of so called auspicious variety] and (hi taṃ saṃsaggiṃ vajjaṃti ya pariharaṃti) positively terminates the affection and withdraws his attachment towards them.

(Ratto jῑvo kammaṃ baṃdhadi) The soul which is encumbered with affection/attachment suffers bondage, while (virāgasamppaṇṇo) one who is unattached and unencumbered (muñcadi) becomes free; (eśo jiṇovadeso) this is laid down by the omniscient [Jinendra Bhagavān]/(tamhā kammesu mā rajja) hence do not indulge in liking/affection for the karma [if you desire freedom/emancipation].

Annotations:

The author commences this chapter with a scathing criticism of the common (but false) belief that auspicious karma puṇya is virtuous and desirable. It will be recalled that puṇya and pāpa (auspicious and inauspicious karma) were included in the list of nine tattvas (categories of truth), each of which is to be discussed, at length, chapter by chapter. This chapter deals with the above two types of karma—puṇya and pāpa—which are the third and the fourth tattvas respectively.

Earlier we have stated that in the process of bondage, karmic matter is attracted and bound with the soul due to the vibrations produced by threefold activities (yoga) as well as passions (kaṣāya). It is necessary to distinguish between these two factors and their functions vis-a-vis bondage of karma. While the intensity of the fruition of karma is determined by the passions, the nature and species of the fruition is determined by the nature of activities of the organism at the time of bondage. The infinitefold activities of a living organism lead to the infinitefold bondage which for the sake of systematic treatment can be classified in various ways. The classification into auspicious and inauspicious is only one such way. The basis for the ascertainment of the activities is moral virtue such as truth, compassion etc.

All activities can be divide into good actions (śubha yoga) and evil or sinful actions (aśubha yoga). Vibrations produced by the former attract auspicious karmic matter while those produced by the latter attract inauspicious karmic matter. The fruition of the former would result in enjoyment of pleasure and the like while that of the latter would result in suffering and misery. Now it is not difficult to see that the good and moral actions result in the bondage of the auspicious types of karma, while evil or sinful ones result in the bondage of inauspicious types. Nevertheless, both are on the same footing with reference to the summum bonum.

Now the bondage of auspicious karma is exclusively due to virtuous activity which is also the means for the attainment of purity of the soul. Here, then, we have a paradox—bondage of puṇya is necessarily concomitant with the partial purification of the soul. It is obvious that one cannot abandon virtuous activities—penance and austerities—to escape the bondage of puṇya. A simple analogy resolves the paradox and shows the way out of the dilemma.

The main function of religious and moral activities—tapas—penance and austerities-is to purify the soul by purging out karmic matter form it (nirjarā). Bondage of puṇya (puṇyabandha) as well as its fruition (puṇyaphala) are incidental products which accompany the spiritual purity much in the same way as chaff is an incidental by-product accompanying the grain which is the essential product of the cultivation of seed. And just as the main purpose of cultivation is the production of grain and not the chaff, so also the aim of a moral action is to purify the soul. Not only the chaff is incidental but unavoidable. The distinction is in the Desire. The desire is to obtain grain in one case and spiritual purity in the other. Just as there is no desire to produce chaff, so also there should be no desire to produce bondage puṇyabandha or its fruition puṇyaphala.

The author, therefore, enjoins the disciple to refrain from desiring the bondage and fruition of puṇya—auspicious karma. "Do not be misled by the sweet-sounding popular adjective 'auspicious', because in reality it is as vicious as pāpa—inauspicious. However, since the bondage itself is unavoidable, what is to be avoided is desire and attachment. One should neither crave for puṇyabandha during religious action nor have longing for the enjoyment of puṇyaphala at the time of its fruition.

Finally, he uses a simple analogy to drive home his point. A person might become friendly and even cultivate intimate relations with another, knowing him to be a good man. But as soon as he comes to know that his friend is really a bad character-in-disguise, he will, immediately, terminate his relationship in order to avoid future damage. Similarly, one may become enamoured with auspicious karma, knowing it to be virtuous. But as soon as he knows the truth that far from being virtuous it is vicious and jetters him to the worldly state, he should terminate his affection for it, that is, experience its fruition impartially.

In the last verse no. 4.6, the author addresses bhavya souls[1] and enjoins them to terminate every kind of attachment and affection from their heart, because even subtlemost attachment to karma albeit auspicious, is a hindrance for emancipation.

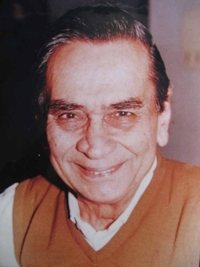

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar