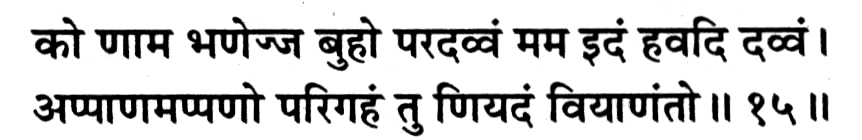

ko ṇāma bhaṇejja būho paradavvaṃ mama idaṃ havadi davvaṃ.

appāṇamappaṇo parigahaṃ tu ṇiyadaṃ viyāṇaṃto..l5

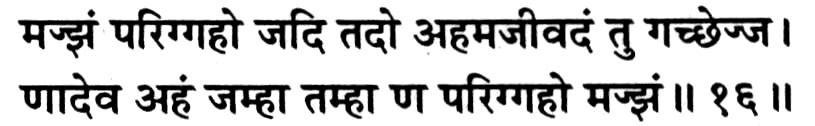

majjhaṃ pariggaho jadi iado ahamajῑvadaṃ tu gacchejja.

ṇādeva ahaṃ jamhā tamhā ṇa pariggaho majjhaṃ..16

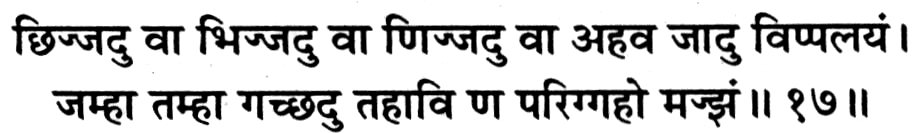

chijjadu vā bhijjadu vā ṇijjadu vā ahava jādu vippalayaṃ.

jamhā tamhā gacchadu tahāvi ṇa pariggaho majjhaṃ.. 17

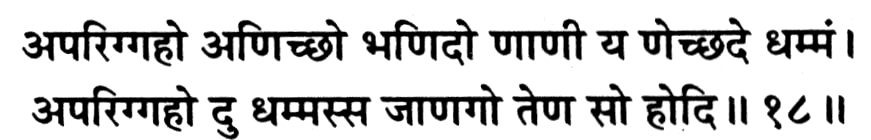

apariggaho aṇiccho bhaṇido ṇāṇῑ ya ṇecchadi adhammam.

apariggaho du dhammassa jāṇago teṇa so hodi..18

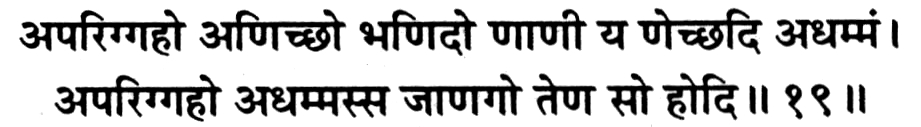

apariggaho aṇiccho bhaṇido ṇāṇῑ ya ṇecchadi adhammam.

apariggaho adhammassa jāṇago teṇa so hodi..19

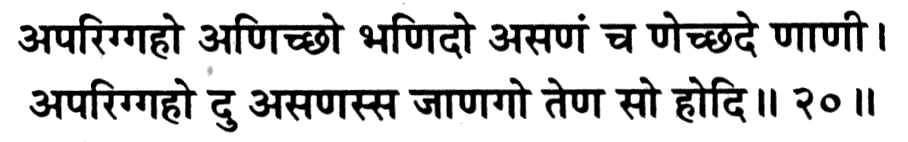

apariggaho aṇiccho bhaṇido asaṇaṃ ca ṇecchade ṇāṇῑ.

apariggaho du asaṇassa jāṇago teṇa so hodi..20

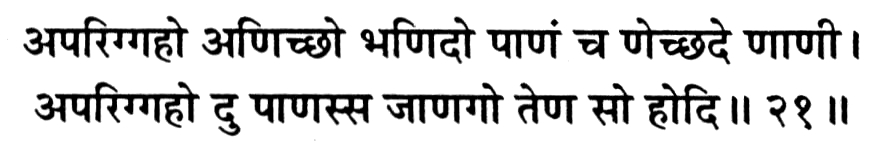

apariggaho aṇiccho bhaṇido pāṇaṃ ca ṇecchade ṇāṇῑ.

apariggaho du pāṇassa jāṇago teṇa so hodi..21

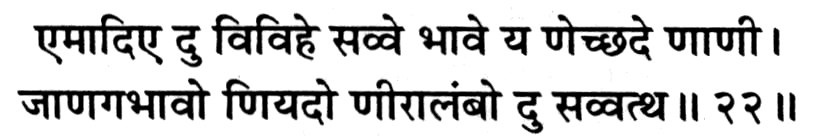

emādie du vivihe savve bhāve ya ṇecchade ṇāṇῑ.

jāṇagabhāvo ṇiyado ṇῑrālaṃbo du savvattha..22

(Appāṇaṃ ṇiyadaṃ appaṇo parigahaṃ tu viyāṇaṃto) Having been convinced that the Self [and nothing else] is the only real [eternal] asset, (ko ṇāma buho bhaṇejja) which wise person will say that (idaṃ paradavvaṃ mama davvaṃ havadi) this alien substance [material wealth etc.] is my asset [possession]?

(Jadi pariggaho majjhaṃ) If I regard the inanimate wealth etc. as my assets [possessions] (tado tu ahamajῑvadaṃ gacchejja) then I [self] [inspite of being endowed with consciousness] would become identical to [becoming] inanimate; (jamhā ahaṃ ṇādeva tamhā pariggaho majjahāṃ ṇa) because I am only 'knower' [i.e., knowledge/consciousness is my own real asset], alien wealth etc. can never belong to me.

(Chijjadu vā bhijjadu vā ṇijjadu vā ahava vippalayaṃ jādu jamhā tamhā gacchadu tahāvi pariggaho majjhaṃ ṇa) [This material wealth [possession] including the body] is liable to be maimed or split or stolen or could be destroyed [in some other way]; whatever the method of dispossession, [I vow that] alien material wealth never belong to me.

(Apariggaho aṇiccho bhaṇido) He who has no desire [for material wealth] is called renouncer [aparigrahῑ] (ya ṇāṇῑ dhammaṃ ṇecchade) and he who is enlightened has no desire for auspicious karma (teṇa so dhammassa du apariggaho) hence, he may be called renouncer of auspicious karma; (jaṇago hodi) he is aware [of the auspicious karma] but has no desire for it.

(Apariggaho aṇiccho bhaṇido) He who has no desire [for material wealth] is called renouncer [aparigrahῑ] (ca ṇāṇῑ asaṇaṃ ṇecchade) and he who is enlightened has no desire for foodstuffs, (teṇa so asaṇassa du apariggaho) hence, he may be called renouncer of food; (jaṇago hodi) he is aware [of the food] but has no desire for it.

(Apariggaho aṇiccho bhaṇido) He who has no desire [for material wealth] is called renouncer [aparigrahῑ] (ya ṇāṇῑ pāṇaṃ ṇecchade) and he who is enlightened has no desire for drinks, (teṇa so pāṇassa du apariggaho) hence, he may be called renouncer of drinks; (jaṇago hodi) he is aware [of the drinks] but has no desire for them.

(Emādie du vivihe savve bhāve ya ṇāṇῑ ṇecchade) Thus, he who is enlightened has no desire for indulging in these and such other sensuous pleasures; (savvattha ṇῑrālaṃbo du ṇiyado jāṇagabhāvo) his sole indulgence is his own characteristic attribute—Knowledge (Consciousness).

Annotations:

In these verses, the author depicts the contemplation and consequent internal dispositions of an enlightened person. In the worldly life, every living organism is, not only associated with a body which one considers its own, but also several other possessions/assets, both animate and inanimate. Even in the case of subhuman organisms, there is such a wider interest than the mere instinct[1] of self-preservation. Of the four primal drives—unlearned instincts—the possessive instinct—parigraha samjñā—identifies the organism with the wider environment in which it lives and survives. Birds, beasts and even insects are known to make out the boundaries of their habitats and possessions and defend them against aggressors sometimes unto death. Their parental and filial instincts are the sub-human basis of institutions of family among humans. In the case of human, several economical and social institutions such as possessing property and belonging to a particular social order or a nation, widen the environmental horizon and extend the personality. Prosperity or adversity of these institutions invoke feelings of joy or sorrow and there is pleasure to possess assets in the form of land, jewels, and other valuable properties. One becomes aggressive if threatened by injury to one's possessions. All these are facts of worldly life and are collectively called empirical reality.

When, with the dawn of enlightenment, one realizes the ultimate truth that all the worldly possessions/assets are transitory in nature and the only eternal assets are one's own inalienable qualities, the horizon and outlook undergoes radical change. Contemplation of the ultimate truth that all material possessions (including the body) are perishable and are most susceptible to being maimed or split or stolen or lost in one way or another, reveals the transcendental reality. How can such a perishable object be considered as identical to Self which is eternal and possessed of the inalienable qualities of consciousness? Identification of material assets to one's self is equivalent to identifying consciousness with inanimate. Realization of this ultimate truth does not necessarily result in physical renunciation of the material assets. The actual realization is in the mental outlook when all desires for alien property disappear.

The change of outlook concerns not only the material possessions but also extends to the auspicious karma (puṇya) and it's fruition which is the transcendental cause of all material assets and their enjoyment. So long as there was a desire for sensuous pleasure, puṇya and puṇyaphala where regarded as the most valuable assets being the ultimate source of all worldly pleasures. But once the desire is subjugated and countermanded by enlightenment, puṇya and pāpa are put on par as the ultimate obstacles to final emancipation.

As the spiritual development advances, carnal desire for all sensuous pleasures diminishes and finally vanishes. An enlightened person does feel hungry and thirsty and he eats and drinks, but there is no psychic response in these physical acts. Slowly all the worldly pleasures lose their charm and the enlightened person for—sakes desire for all worldly dispositions and he is content with their awareness.

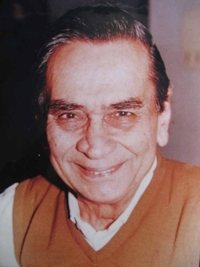

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

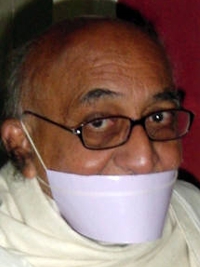

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar