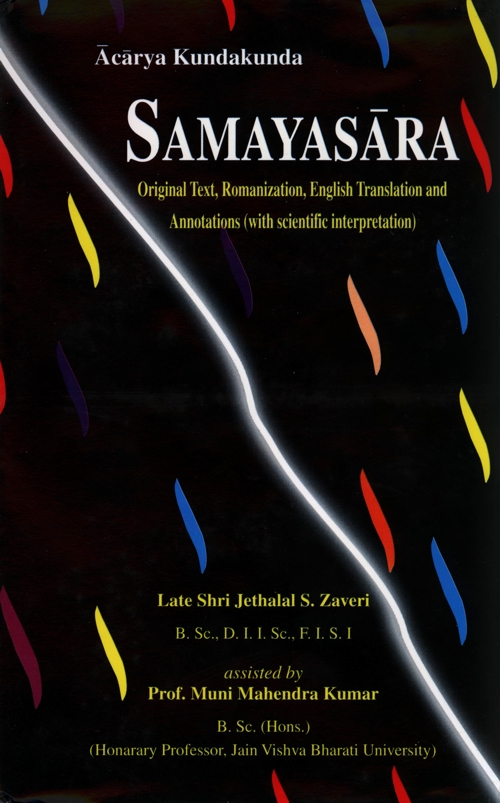

paṇṇāe ghettavvo jo cedā so ahaṃ tu ṇicchayado.

avasesā je bhāvâāte majjha pare tti ṇādavvā..10

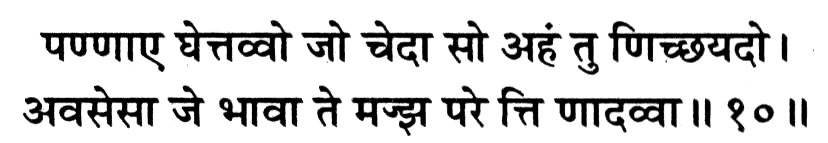

paṇṇāe ghettavvo jo daṭṭhā so ahaṃ tu ṇicchayado.

avasesā je bhāvā te majjha pare tti ṇādavvā..11

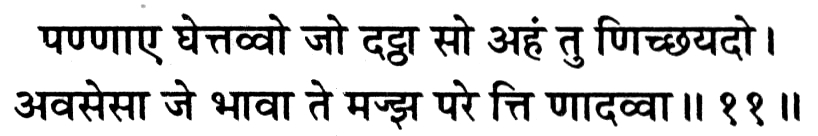

paṇṇāe ghettavvo jo ṇādā so ahaṃ tu ṇicchayado.

avasesā je bhāvā te majjha pare tti ṇādavvā..12

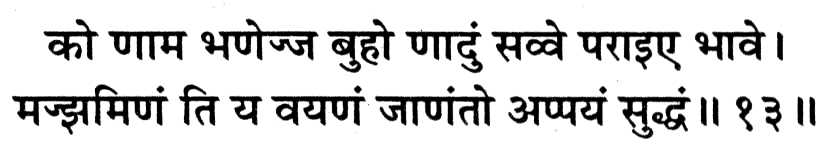

ko ṇāma bhanejja buho ṇāduṃ savve parāiye bhāve.

majjhamiṇaṃ tiya vayaṇaṃ jāṇaṃto appayaṃ suddhaṃ..13

(Paṇṇāe) By instrument of discriminative wisdom, (ghettavvo) [one] should apprehend [that] (jo cedā) that which is [pure and eternal] consciousness, (ṇicchayado) is, in actual reality, (so tu ahaṃ) the Self; [and also] (avasesā je bhāvā te majjha pare tti ṇādavvā) it should be known (realized) that whatever other psychic states were left behind are alien to the Self (i.e., are non-self).

(Paṇṇāe) By instrument of discriminative wisdom, (ghettavvo) [one] should apprehend [that] (jo daṭṭhā) that which is 'seer', (ṇicchayado) is, in actual reality, (so tu ahaṃ) the Self; [and also] (avasesā je bhāvā te majjha pare tti ṇādavvā) it should be known (realized) that whatever other psychic states were left behind are alien to the Self (i.e., are non-self).

(Paṇṇāe) By instrument of discriminative wisdom, (ghettavvo) [one] should apprehend [that] (jo ṇādā) that which is 'knower', (ṇicchayado) is, in actual reality, (so tu ahaṃ) the Self; [and also] (avasesā je bhāvā te majjha pare tti ṇādavvā) it should be known (realized) that whatever other psychic states were left behind are alien to the Self (i.e., are non-self).

(Appayaṃ suddhaṃ jāṇaṃto) Knowing [the ultimate truth] that the Self is the pure [Self and nothing else] (savve bhāve parāie nāduṃ) and having known that all [other] psychic dispositions are alien, (i.e., non-self), (ko ṇāma buho) which wise man (majjhamiṇaṃ ti ya vayaṇaṃ bhaṇejja) would make such statement as they (those dispositions) are mine?

Annotations (on Verses 9.6 to 9.13):

In these eight verses (9.6 to 9.13), the learned author prescribed an infallible technique for separating and isolating the pure self and directly experiencing it in its most fundamental state. This, in fact is the process of Bhedavijñāna. In the preceding verses, we discussed the achievement of liberation from the bondage and concluded that, just as a person bound with chains in worldly life, achieves freedom only by breaking the chains, so also, the self attains emancipation only by breaking the bondage of karma. Now in these verses, a reliable method for breaking the chains is prescribed.

Earlier we have already said that in the worldly existence, bondage of karma is a real condition of the self (soul) and though existing from the beginningless time as coeval with the individual, yet it is amenable to be transcended. Final liberation/emancipation is nothing but the disentanglement of the self from the non-self which is karmic matter. It should be remembered that 'demolition of karma' does not mean destruction of karmic matter which is not destroyed but pulled out and separated from the soul. Just as gold, in its natural state is found to be corrupted with impurities in the form of ores from the very emergence of its being, but can be disentangled from it, i.e., purified by a chemical process, so also the self can be disentangled, i.e., purified by a spiritual process. The pure self which is realized is not a new creation in the absolute sense like the pure gold. It was always there but polluted and obscured by the impurity of the karmic matter. In the state of emancipation, the pollution and the obscuration are ended once and for all. The above verses describe the process and technique of spiritual purification.

The process of disentanglement (of the Self from the Non-self) is a based on the fact that the characteristic attributes of each is fundamentally different and the difference is recognizable. As in the case of gold the nature and worthlessness of the corrupting ore is known, so also the nature and worthlessness of the polluting karmic matter is known. And so, the first step in the process of separation prescribes that the beginningless infatuation for the worthless karmic matter and its bondage must be abandoned.

Now a process of separation envisages the need of an apparatus which must be reliable and capable of doing the job efficiently. Also the apparatus must be equipped with a proper tool. Here the author prescribes a chisel-like tool which if used properly, is capable of producing a well marked line of cleavage between the two entities and make them fall apart. Such a tool is called Discriminative Wisdom (Prajñā).

And how is this wonderful instrument, discriminative wisdom (prajñā) to be secured? It is obtained by developing the capacity for Self-concentration/Self-meditation. For this, firstly it is necessary to concentrate upon the self as distinct and separate from the body. The soul acquires more and more power for self-concentration (meditation) along with the increase of its purity and consequent attainment of the corresponding stages of spiritual development. When one is able to, mentally, separate the self from the body and is fully convinced of the distinction between the self and the non-self, the next step is to rise still higher and concentrate upon the pure transcendental self which is free from all the limitations of the empirical self. The most important factor in favour of self-meditation, for this purpose, is the fact that both the empirical self and the transcendental self are intrinsically possessed of the same attributes which are unmanifested or less manifest in the former and fully manifest in the latter. To understand fully the method of self-meditation, three states of self are distinguished, viz., the exterior self, (bahirātmā), the interior self (antarātma), and the transcendental self (paramātma). The exterior self is the common empirical ego with the deluded belief that it itself is identical to the body. The interior self, clearly, discriminates itself from the Body, Sense-organs and Mind. The transcendental self is the pure and perfect self which is free from all limitations as well as psychological distortions. Self-meditation is, further based on the conviction that the transcendental self is the self-realization of the exterior self through the intermediary stage of the interior self.

As the capacity of self-concentration develops, the sharpness and the separation power of the instrument (wisdom), increases and the interior self—the state of the self prior to the attainment of omniscience—is realized. And finally, the instrument completes its job by the attainment of omniscience when the self becomes the transcendental self (paramātma). Thus self-meditation leads to self-realization.

In the following verses, the highly developed self-meditation is equated with self-adoration or self-idolisation and concentrated and continuous adoration of the pure (transcendental) self culminates in final liberation. The self-adoration is equivalent to Rupātῑta Dhyāna. We shall now see the modus operandi of this wonder instrument.

Pure consciousness is the unalienable characteristic attribute of pure self, while the attributes which characterize the alien bondage of karma are perverted belief and impure psychological distortions such as cruelty. In the worldly state of existence, both are entangled together from the eternity. The instrument of separation is equipped with a sensor which fully realizes the pure nature of the inherent attribute of the self and thereby identifies it. It also senses the impurity of the emotions, passions and such other psychological distortions produced by the bondage and identifies them as alien. Having identified the two entities, the chisel of discriminative wisdom begins to chip and ultimately splits them apart. The debris of non-self is then disentangled and the Pure Self is revealed in its unpolluted state. Once split asunder, the two entities remain separated.

Continuing the process, the author prescribes the next important step. After separation, the self and the non-self stand apart, each with its own characteristic attribute. So in the next step, the worthless debris of the bondage is cast off and the pure self in its fundamental state is recovered and realized.

At this stage, a junior disciple raises a query: "Sir, you say that the pure self is to be recovered, collected and realized; but how can one collect the pure soul'?" The Ācārya replies that it is not only possible but easy to recover the self after it has been separated from the non-self. The very same apparatus which split the self and the non-self apart and isolated the pure self, is to be used for collecting and recovering the pure self. The apparatus—discriminating wisdom—besides possessing the tool for splitting the entities, is also equipped with the ability to directly experience/apprehend the pure soul. It can grasp, collect and realize the self just as it can separate and isolate it from the non-self.

To fully understand the process of recovering the self after separation, we must briefly review the nature of the pure self with its inalienable characteristic qualities. Consciousness is the very essence of the self and is integral to it. Though change is also integral and inherent in whatever is real, and as such the self also must be changing, consciousness being the very stuff and texture of the self, there is not a single moment in which the self ceases to be free from consciousness. In the emancipated pure state, the self and consciousness, which are inseparable though not interchangeable, are free from all obscurents and obstructions of the worldly state. This is omniscience. And what has been said about pure consciousness is also applicable to pure intuition and pure knowledge.

Now, according to the law of anekānta, even the pure self cannot be abstracted from all its attributes as is believed by the absolutist philosophies (e.g. Vedānta). Here Ācārya Kundakunda emphasizes that while impure attributes such as psychological distortions are abstracted, being alien to pure self, the pure attributes, such as pure knowledge or pure perception/intuition, are not abstracted being inalienable qualities even after the final liberation. Of course, these attributes are not the same as those associated with worldly state, because in this state, knowledge and intuition/ perception (though designated by the same terms) are grossly limited by physical conditions. On the other hand, the pure knowledge etc., associated with pure self are the unconditional and unlimited manifestations of the pure self.

Based on these facts of the law of anekānta, the author prescribes the technique for grasping and recovering the self. (1) Pure consciousness (2) the seer, and (3) the knower are inseparable from the pure self and are therefore real. Besides these, whatever psychological dispositions are there, should be left behind and cast off, because they are neither T nor 'mine'. Applying this technique, the process of self-realization succeeds in collecting and holding the pure self. And having successfully realized one's real self, can any wise man still continue to maintain that those (cast off emotions produced by bondage of karma) are mine?

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar