30

The Goddesses of Sravana Belgola [*]

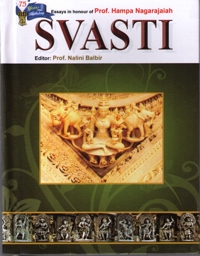

The pilgrimage shrine of Sravana Belgola is, without a doubt, one of the best-known sacred sites of the Jains, and its 58-foot tall colossal icon of Bāhubali, carved out of the very rock in the late tenth century, is one of the sculptural wonders of the world. The periodic great lustration (mahāmastakābhiṣeka) of the icon attracts hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, tourists and scholars to this otherwise small and quiet town in Karnataka. Photographs of the event, and more recently YouTube postings, spread throughout the world by newspapers, magazines, and now the internet. In many ways the icon of Bāhubali has become emblematic of Jainism as a whole. Robert Zydenbos, for example, in his 2006 popular introduction to Jainism, chose a photograph of the most recent (2006) lustration for the cover to the book, and Jeffery Long similarly chose a photograph of the ludic and celebratory response of devotees to the same lustration for the cover of his 2009 introductory textbook on Jainism.

Focusing solely on the ways that the icon of Bāhubali graphically demonstrates the Jain renunciatory ideal of liberation (mokṣa), however, results in both scholars and most pilgrims overlooking the other living heart of the sacred complex: the goddess. It is her presence, ritually installed and daily worshiped, at multiple locations that, in the eyes of Jain devotees, protects and vivifies the site.[1]

Southern Digambara Jainism is known for the prominent place given to worship of goddesses. In this it stands in distinct contrast to the ways that northern Digambara Jainism has developed in the past three centuries due to the anti-goddess ideology of the Digambara Terāpanth. Goddess worship still maintains a place in the ritual culture of the Digambara Bīspanth, but is much reduced compared both to earlier centuries and to patterns in south India. In particular, there are three goddesses who are very popular among Digambara Jains of Karnataka.

Padmāvatī is the yakṣī or śāsanadevī who guarded the twenty-third Jina Pārśvanātha, and who continues to guard his tīrtha as embodied in his icons and shrines. She is a goddess who is equally popular in south and north India, and among Digambaras and Śvetāmbaras (Cort 1987: 244-46). In Karnataka, her most important shrine is at Hombuja or Humcha, in Shimoga District.[2] The Hombuja icon is said in the sthalapurāṇa or foundation myth of this shrine to have come from Madhure (Mathura) in north India. King Jinadatta was forced to flee to the south, and at the advice of his guru, the monk Siddhāntakīrti, he brought the icon of Padmāvatī to protect him on his journey. At one point she appeared to Jinadatta in a dream, and told him that she would travel no further. He became king of the local tribals, and with their aid cleared the forest and built his new capital city. Padmāvatī made him rich by turning into gold any iron bar that was touched to her icon. This was the beginning of the Śāntara dynasty. Her icon in Hombuja remains a popular pilgrimage goal among Karnataka Jains today.

In contrast to Padmāvatī, Jvālāmālinī is a more distinctly southern Digambara goddess in her popularity. According to Jain iconography and mythology, she is the yakṣī or śāsanadevī of the eighth Jina, Candraprabha, but in many respects her cult is independent of his.[3] There are two origin stories found for her worship. One involves the ninth-century Jain monk Helācārya. He worshiped a local goddess named Vahnidevī, who resided atop a hill in North Arcot District of Tamilnadu, in order to rid his female disciple Kamalāśrī of a fierce demon that had possessed her. The goddess gave Helācārya a mantra, and he incorporated her into Jainism as the goddess Jvālāmālinī. In the other version, the great sixth-century philosopher-monk Samantabhadra was a devotee of Jvālāmālinī. He was afflicted with a seemingly incurable disease. His own guru recommended that he go to the Śaiva shrine of Kanchi, where due to her grace he was eventually cured. It is this latter story that is told at her most important shrine in Karnataka, at Simhanagadde or Narasimharajapura, in Chikmagalur District.

The third goddess is Ambikā, better known in Karnataka by her alternate name Kuṣmāṇḍinī. She is also popular in both north and south India, and among both Digambaras and Śvetāmbaras.[4] Her origin story is located in Saurashtra, in Gujarat. A pious Jain laywoman named Ambikā was forced to flee her home along with her two sons due to the anger of her husband, a Brahmin named Soma. During their wandering, several miracles occurred due to the woman’s piety. When her husband eventually ran after her to bring her back, she feared more violence, and so she and her sons jumped into a well to save themselves. She was reborn as the goddess Ambikā, who was the yakṣī or śāsanadevī of the twenty-second Jina, Neminātha. That he was the one Jina who was born, lived, and attained liberation in Saurashtra confirms the regional origin of her myth. Her story also conforms to those of many Saurashtrian and Gujarati goddesses, who are the reincarnations of virtuous and pious women who died from unfortunate and violent causes.

30.1Kuṣmāṇḍinī in Karnataka is especially associated with Sravana Belgola, for she is the guardian deity of the site. Robert Zydenbos (2000:87-88) has observed that each of the three important goddess shrines is also the seat of a bhaṭṭāraka, so we see that these two distinctive aspects of southern Digambara ritual culture are closely connected. At Hombuja and Simhanagadde, the largest temples - and so putatively the main ones- are of the Jinas Pārśvanātha and Candraprabha, respectively. Even a cursory observation of the attention of pilgrims indicates, however, that most if not all of them come primarily to worship the goddesses, not the Jinas. At Sravana Belgola, on the other hand, there is no central temple of Neminātha, as one would expect since Kuṣmāṇḍinī is his śāsanadevī. There is no mythic or iconographic connection between her and Bāhubali. Her role as guardian of the shrine, therefore, either precedes the consecration of the Bāhubali icon in 981 A.D., or else further shows how the cults of the Jain goddesses in Karnataka are only loosely tied to those of the Jinas.

30.2The principal icon of Kuṣmāṇḍinī is not on either of the two hills, but in a cell in the temple to the Jina Candraprabha (also known here as Candranātha) next to the maṭha (monastery) that is the seat of the bhaṭṭāraka (Plates 30.1, 30.2).[5] The doorway to her cell is gilt with gold, adding to her luster. This icon is worshiped daily by ablution (abhiṣeka) and offerings (pūjā). While this temple is not visited by many pilgrims, who tend to focus their devotional attention upon the icon of Bāhubali on Vindhyagiri, a small number of people come every day to receive her sacred gaze (darśana). Tuesday is the day of the week devoted to Kuṣmāṇḍinī, so more people come for her gaze on that day. Her icon is elaborately adorned every day with a tall silver crown, silver and jeweled ornaments, flowers, and silk cloth, so her darśana is a visually rich experience. Kuṣmāṇḍinī is not the only goddess in this temple, as there are also icons of Padmāvatī and Jvālāmālinī, both of which are also worshiped and elaborately decorated every day.

30.3Kuṣmāṇḍinī, not surprisingly, since she is the guardian of the sacred site, is also present atop Vindhyagiri, the hill topped by the Bāhubali icon. She is not a very prominent presence, however. Her icon is located in a cell among a number of other cells with icons of Jinas in the pavilion that runs behind the Bāhubali icon (Plate 30.3). While this icon is worshiped daily, on most days she is ornamented much more simply than the other important goddess icons at Sravana Belgola, with just a long garland of red and white flowers around her neck.

The third important and popular icon of Kuṣmāṇḍinī is atop Candragiri. Compared to the steady stream of pilgrims up Vindhyagiri to worship the icon of Bāhubali, a much smaller number of people climb Candragiri, even though this hill is covered with temples, and is the older of the two sacred hills. Only a few icons in the more than one dozen medieval temples receive much active worship. Pilgrims who climb this hill tend to take a quick darśana of the many Jina icons. The people who linger to read the many signs posted by the Archaeological Survey of India, and to inspect the architecturally and iconographically important structures, are acting as much as tourists as they are pilgrims. Their gaze is as much a secular and historical one as it is religious.

30.4Many of the people who engage in this historical viewing of Candragiri may pay very little attention to two cells on the veranda of the largest temple on the hill, the Kattale Basati, or “dark temple”, so called because the lack of windows renders it very dark inside. This temple, with its main icon of the Jina Ādinātha, was built in 1118 A.D. by Gaṅgarāja, a minister of the Hoysala king Viṣṇuvardhana, in honor of his own mother Pocikabbe, and renovated in the mid-nineteenth century by two women of the Mysore royal family.[6] While the icon of Ādinātha is, in the words of one author (Nagaraj 1981, 16), “a fine piece of Hoysala art,” it is not the main focus of worshipers. They come instead to view and worship the icon of Padmāvatī, and her devotional centrality has lent this temple its second name, Padmāvatī Basati.[7] The attentive pilgrim or tourist will note that her icon, as well as the icon of Kuṣmāṇḍinī in a nearby cell, and an icon of the male protector deity Kṣetrapāla in a third cell, give evidence of frequent worship. Their icons are ornamented, the smell of incense is in the air, and offerings are on the low tables at the entrances to the cells. Each goddess cell also has a rod running from wall to wall across the width of its inside, on which dozens of women devotees have left glass bangles, in response to a petition that has been successfully answered. Of the two goddesses, Padmāvatī is more popular here, as seen in her more extensive ornamentation (Plate 30.4). The priests (arcaka) who perform the daily morning worship of the two goddesses pay more attention to Padmāvatī than to Kuṣmāṇḍinī, especially on Fridays, the day dedicated to Padmāvatī. The people who come to worship her on that day are almost exclusively Jains who live in the village of Sravana Belgola.

30.5On that day she receives four ablutions, of water, milk, water with sandalwood paste mixed in it, and finally water again (Plate 30.5). The icon is then dried off and ornamented. The priest goes outside the temple to crack open a coconut, and brings the two halves inside to offer before the goddess. He then performs the standard eight-fold worship (Vasantharaj 1985), concluding with the performance of āratī, the waving of a flaming lamp in front of the icon. He brings the metal plate with the lamp on it out of the cell for onlookers to wave their hands above the flame and then touch their hands to their faces as blessing. In return, some of the onlookers place a small monetary offering on the plate. Next the priest brings the bowl used to collect the ablution liquid, and uses a flower blossom to sprinkle the water on the onlookers, while speaking a Sanskrit mantra that says that this blessed water will remove all sins (pāpa), and result in all one’s undertakings being successful. Finally he hands the two halves of the broken coconut to the lay person who has been the patron for that day’s worship, who in turn breaks it into smaller pieces to distribute to everyone present. This worship is the same as that performed to an icon of a Jina and to the large icon of Bāhubali, with the only exception being that the Sanskrit mantras are directed to Padmāvatī (and then Kuṣmāṇḍinī) instead of to a liberated being.

30.6While the icon of Padmāvatī in the Kattale Basati atop Candragiri is believed to be the oldest Padmāvatī icon at Sravana Belgola, and so plays an important role in the protection of the entire site, another icon of her in the village is more popular, in large part because it is much more easily accessible. Across a square from the maṭha of the bhaṭṭāraka is the Bhaṇḍārī Basati, the largest temple in the entire sacred complex. It is so-called because it was commissioned in 1159 by Hullarāja, the treasurer (bhaṇḍārī) of the Hoysala king Narasiṃha I, who in turn dedicated the income of a village to its upkeep (Sangave 1981, 18-19). It is also known as the Caturviṃśati Tīrthaṅkara Basati, because instead of a single main icon, its main altar area contains a row of nearly identical icons of the twenty-four Jinas. On either side of the large pavilion in the front part of the temple are two cells, one containing an icon of the important male deity Brahmadeva,[8] and the other an icon of Padmāvatī (Plates 30.6, 30.7). Both of them receive regular attention from worshipers, especially early in the morning and in the evening. Some people even come for darśana of these two deities and do not proceed further into the temple for darśana of the Jina icons. There is a string of bangles in the cell of the Padmāvatī icon. While these may be given to her in response to the granting of many different petitions, they are given most often as thanks for the safe birth of a child, and local women regularly bring infants to this shrine to be blessed by the goddess.

30.7We have seen that while Sravana Belgola is best known to pilgrims, tourists and art historians for the monolithic icon of Bāhubali, careful attention to ritual and devotional activity reveals a second sacred focus upon the goddess in two Jain personalities, Kuṣmāṇḍinī and Padmāvatī. Jvālāmālinī, the third highly popular goddess among Digambara Jains of Karnataka, has a much less visible presence in the sacred complex. Also less noticeable in their presence are two goddesses whom the Jains share with the larger South Asian religious world, although they also have distinctive Jain cults and personalities: Lakṣmī and Sarasvatī.[9] Any sacred site will accumulate multiple meanings, as centuries of pilgrims, residents and religious specialists leave their traces in memory, constructions, and the very rocks themselves.[10] Some of these meanings will be evident to everyone, as they are embedded in the most public and obvious rituals and objects. These may come to be iconic for the entire site. But scholars must be attentive to more than the obvious. In the case of Sravana Belgola, such sustained observation and analysis is rewarded with the revelation that the goddess is a vital, even essential presence.

Works Cited

Ādisāgar, Brahmacārī. N.d. Śrī Pārśva-Padmāvatī Rocak Kahānī. Imphal: Vijay Pāṭnī.

Cort, John E. 1987. “Medieval Jaina Goddess Traditions.” Numen 34, 235-55.

-. 2001. Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. New York: Oxford University Press.

-. 2006. “Installing Absence? The Consecration of a Jina Image.” In Robert Maniura and Rupert Shepherd (eds.), Presence: The Inherence of the Prototype within Images and Other Objects, 71-86. London: Ashgate.

-. 2007. “Saraswati, Goddess of Knowledge and Scripture.” In Nagarajaiah, Hampa (chief ed.), Sumati-Jñāna: Perspectives of Jainism: A Commemoration Volume in the Honour of Ācārya 108 Śrī Sumatisāgara Jī Mahārāja, 153-58. Muzaffarnagar: Acharya Shanti Sagar Chhani Smriti Granthamala.

-. 2008. “Pilgrimage and Identity in Rajasthan: Family, Place, and Adoration.” In Lawrence A. Babb, John E. Cort and Michael W. Meister, Desert Temples: Sacred Centers of Rajasthan in Historical, Art-Historical, and Social Contexts, 93-114. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

del Bonta, Robert J. 1981. “The Temples and Monuments.” In Saryu Doshi (ed.), Homage to Shravana Belgola, 63-100. Bombay: Marg Publications.

Deśmāne, Vidyullatā Vidyādhar. 1987. Śrī Kuṣmāṇḍinī Devī, Śravaṇa Beḷgoḷa. Mumbai: Śrī Kailāscandra A. Raṇdive.

Ghosh, Niranjan. 1979. Concept and Iconography of the Goddess of Abundance and Fortune in Three Religions in India. Burdwan: University of Burdwan.

Granoff, Phyllis. 1990. “The Origins of a God and Goddess, from a Medieval Pilgrimage Text, the Vividhatīrthakalpa of Jinaprabhasūri.” In Phyllis Granoff (ed.), The Clever Adulteress and Other Stories, 182-88. Oakville, Ont.: Mosaic Press.

Joyis, Bhuvanhalli Ḍi. Śrīpatī. 1996. Atiśay Kṣetra Hombuj / Athishaya Ksethra Hombuja. Hombuja: Siddhāntakīrti Granthmālā.

Karnataka, Government of. 1981. A Guide to Sravana-Belgola. Mysore: Govt. Text Book Press.

Long, Jeffery D. 2009. Jainism: An Introduction. London: I. B. Tauris.

Nagaraj, Nalini. 1980. Sravanabelagola. Bangalore: Art Publishers of India.

Nagarajaiah, Hampa. 2001. Opulent Chandragiri. Sravanabelagola: S. D. J. M. I. Managing Committee.

-. 2005. Bāhubali and Bādāmi Calukyas. Shravanabelagola: SDJMI Managing Committee.

-. 2009. Spectrum of Sarasvatī: Śrutadevī. Shravanabelagola: National Institute of Prakrit Studies and Research, Bahubali Prakrit Vidyapith.

Sangave, Vilas A. 1981. The Sacred Śravaṇa-Beḷagoḷa (A Socio-Religious Study). Delhi: Bharatiya Jnanpith.

Settar, S. 1969. “The Cult of Jvālāmālinī and the Earliest Images of Jvālā and Śyāma.” Artibus Asiae 31, 309-20.

-. 1971a. “The Brahmadeva Pillars: An Inquiry into the Origin and Nature of the Brahmadeva Worship among the Digambara Jains.” Artibus Asiae 33, 17-38.

-. 1971b. “Chakreśvarī in Karnāṭak Literature and Art.” Oriental Art (N. S.) 17, 63-69.

-. 1981. Śravaṇa Beḷgoḷa. Dharwad: Rūvāri.

Shah, Umakant P. 1940. “Iconography of the Jain Goddess Ambikā.” Journal of the University of Bombay 9, 147-69.

-. 1941. “Iconography of the Jain Goddess Sarasvatī.” Journal of the University of Bombay 10, 195-218.

-. 1971. “Iconography of Cakreśvarī, the Yakṣī of Ṛṣabhanātha.” Journal of the Oriental Institute 20, 280-313.

-. 1987. “Origin of the Jaina Goddess Ambika.” In B. M. Pande and B. D. Chattopadhyaya (eds.), Archaeology and History: Essays in Memory of Shri A. Ghosh, Volume 2, 483-94. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

-. 1991. “Two Interesting References by Haribhadra Suri.” In Chandramani Singh and Neelima Vashishtha (eds.), Pathways to Literature Art and Archaeology: Pt. Gopal Narayan Bahura Felicitation Volume, Volume 1, 60-64. Jaipur: Publication Scheme.

Suprakāśmati, Āryikā. N.d. Siṃhanagadde (Jvālāmālinī) Kṣetra kā Saṃkṣipt Paricay. Enarpura: Bastimaṭh Enārpurā.

Tiwari, M. N. P. 1989. Ambikā in Jaina Art and Literature. New Delhi: Bharatiya Jnanpith.

Vasantharaj, M. D. 1985. “Puja or Worship as Practiced Among the South Indian Jainas.” In Third International Jain Conference Souvenir Volume, 98-101. New Delhi: Ahimsa International.

Zydenbos, Robert J. 1992. “The Jaina Goddess Padmavati.” In K. I. Koppedrayer (ed.), Contacts Between Cultures: South Asia, Volume 2, 257-62. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.

-. 1994. “Jaina Goddesses in Kannada Literature.” In Alan W. Entwistle and Françoise Mallison (eds.), Studies in South Asian Devotional Literature, 135-45. New Delhi: Manohar; and Paris: École Française d’Extrême-Orient.

-. 2000. “The Concept of Divinity in Jainism.” In Joseph T. O’Connell (ed.), Jain Doctrine and Practice: Academic Perspectives, 69-94. Toronto: University of Toronto, Centre for South Asian Studies.

-. 2006. Jainism Today and Its Future. München: Manya Verlag.

All photographs reproduced with this article are by the author

This short essay is based on fieldwork conducted in Sravana Belgola in 1999 and 2008. In both cases, research was funded by a Senior Short-Term Fellowship from the American Institute of Indian Studies. I thank Robert Zydenbos and Nagarajaiah, Hampa, for their assistance in organizing my two visits to Sravana Belgola (and much else). I also thank H. H. Swastishri Carukirti Bhattaraka and Dharanendra Shastri for their hospitality at Sravana Belgola.

Prof. Dr. John Cort

Prof. Dr. John Cort