Society functions on the basis of tradition. Truth, when it is linked with tradition, comes down to the ground of practical reality. We have before us Bhagwan Mahavira's religious tradition. He had started the tradition of establishing Dharma Sangha 2500 years ago. His preachings were compiled 1000 years later, after which in the course of the long period of 1500 years, new concepts were formed on the basis of those compilations. Conditions prevailing at various times provided scope of doing research on those concepts, in the course of which some old values got dissipated and were replaced by new values. Unless we understand the changes during the intervening period, we find incoherent elements in the past and the present.

The phenomenon of change is a perpetual feature of the world. No one can stop it. According to the Jain philosophy, the eternal nature of things is based only on constant change. There is no steadiness which is devoid of origination and cessation. Like the change in things, change in values also follows a certain principle. Only on that basis the individual can bring about changes in this thinking, beliefs and behaviour.

Change is the background for creation, without which the individual gets frustrated by his personal situations, and he loses the capacity to live with his times. In the social field, non-acceptance of change leads to conventionalism, which is a very big obstruction in the way of experimentalism.

The principle of change is acceptable to those people who are familiar with the contexts of their country, their times and the prevailing conditions. Those who are unfamiliar with history, find change irksome. Those who do not understand the distinction between the permanent and the periodic, cannot understand change either. That which is permanent never changes. However, rules are subject to change in accordance with the change in time and place. How can the change in what is changeable be unnatural? It is extremely important to study the phenomenon of change of order to study thoroughly the individual and the community.

Those who consider the principal great vows and samachari[1] as absolutely identical get caught in confusion at every step. Whenever there is an Order (Sangh), there has to be organisation samachari is related to the changing conditions of time, place and circumstances.

The mutual relations of the monks, the mutual relations of the nuns, relations of the monks and the nuns with the householders, their usage of medicines, their routine for going for alms, daily time-table, and other topics like their clothes, utensils, etc. are prescribed as samachari.

Behaviour which is in conformity with samachari is called kalpa and that which is contrary to samachari is called akalpa. The samachari mentioned in the ancient sutra is found in a changed form in the commentaries like Bhashya- Churni etc. which, in turn, have undergone a change in the present times.

Those who make a serious study of ancient literature are not unfamiliar with the changed forms of samachari. They are not even surprised by those changes. Only those people find these changes surprising who do not study the ancient treaties seriously and with an open mind. I wish the people who are interested in this subject devote themselves to serious study.

Is there any field which is free from change? Change breathes new life in all fieldseconomic, social, political, spiritual. It is due to change that consciousness develops. Change is not irrelevant in any situation, provided its purpose and basis are clear and well-supported. Through the change undertaken for creativity on the ground of ioality, one can discharge ones responsibility towards the past and the future.

I am committed to the tradition of a religious order. Since I am incharge of the management of my Sangh, I have full faith in those traditions and I am always alert. But I am not insistent about them in any way. Insistence is a very big obstacle in the path leading to truth. Acharya Yashovijayaji has explained this by a metaphor: "The mind of an insistent person is like a monkey. He catches hold of the tail of a cow (truth) and pulls it towards himself. The mind of a person who does not insist is like a calf. Therefore, it carefully follows the cow." Non-insistence is the clear way to understand truth.

In my view, every tradition demands change in the context of the changed circumstances. He who does not see this need, cannot be just to his times. In the past two decades, I have thought very freely about some of our traditions and have also made the necessary changes in them. I can see full scope for revising my thinking in the future as well.

Bhagwan Mahavira, in his own times, introduced changes in the traditions established by Bhagwan Parshva. History vouchsafes this. The testimony of the past is the strong basis for the present. From that point of view, I strongly uphold change. Some conducive evidences have also been of help. Even if those evidences are not strong enough, in the absence of obstructive evidences, there is scope for change. There are some realities whose basis is not available or they have outlived their importance. We can also give some thought to such realities.

According to a particular scriptural tradition, it is absolutely necessary for a Dharma Sangh to have the preceptor {acharya), a teacher (upadhyaya) and a head-nun (pravartani). The monks and the nuns are expected to live only under their guardianship. Acharya Bhikshu modified that tradition to an extent and entrusted the entire responsibility of the Sangh to a single person (acharya). If need be, this new tradition may again be practised in its original form. Those who do not understand the propriety of principle of change, would find themselves disturbed in such situations.

In the middle ages, while dismissing asceticism, Acharya Haribhadra wrote in Sambodha Prakarana: "That ascetic who covers himself with a shoulder-cloth, even while living in an upashryas[2] and exchanges food etc. with the nuns, is given to lax conduct." However, this definition of lax behaviour becomes somewhat loose. The acharyas who came later, supported the earlier restrictions and the past tradition was left behind. The illusions resulting from prohibiting and supporting certain behaviour can be dispelled only by the principle of relative consideration of time and place.

Acharya Bhiksh set new limits in this regard in his own time. He mentioned certain important points so that the limitations applied to the management of the Sangh and organisation do not lead to any complications any time:

- If some new facts with regard to the scripture and principles are discovered, the versatile ascetics should discuss them but should not resort to obstinacy.

- The conventions and traditions prevalent at present may be changed by the future acharyas. They can make changes or modifications in them if they think that they are necessary.

By giving to the future acharyas the right to change the tradition, Acharya Bhikshu showed his inclination to search truth. Acharya Bhikshu is the founder of our Dharma Sangh (Terapanth).

I have great faith in him. By introducing certain changes in the traditions that have come down to us from his time, I have only acted in the light of the attitude of search for truth he had inspired in me. I have no doubt at all that those traditions were necessary in those days. Since I could not see their utility in the present time, some changes have been introduced in them.

Some people question the propriety of changes I have made. How the changes were made and what is their basis? Are these changes in conformity with the scriptures?" These are some of their questions which reflect their inquisitive minds. I consider this a good sign. Curiosity to know about any new reality is not unnatural. Mental conflicts can be resolved only by such curiosity. Progress in the field of science is only the result of human curiosity. Every new scientific discovery leaves a scope for the revision of any pre-conceived ideas. Without that no scientist in the world could find any scientific truth.

It is necessary to have the inclination towards truth in order to understand the facts. The individual inclined towards truth does feel curious when he notices new things happening, but there is no dissatisfaction in his mind. Dissatisfaction is related to mental impatience. I do not wish to see any followers overcome by dissatisfaction in any way. That is why I always want to answer their questions. Some of their questions come to me directly and about some I hear.

Whatever it may be, these questions do not pertain to any single individual or place. These questions are being discussed everywhere. That is why I felt that they should be collectively answered from a central place. Thereby, not only the concerned subject would be placed in the correct perspective, the basis and purpose of the change too would be understood. I do hope that my friends who are eager to know about these things, would try to understand me as well.

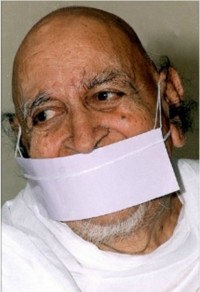

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi