| International Conference on Jainism Through the AgesA Historical Perspective8th, 9th & 10th October 2010 Mysore, India |

Some Turning Points in the History of Jaina Religion and Philosophy

It is sometimes said that there has not been any appreciable development in the history of Jaina philosophy. The fact is that from time to time, there have been made such startling statements in Jaina works, that stand apart from the common rut of Jaina thought. Sometimes such statements have been overlooked, sometimes they gave birth to controversy and sometimes they led to schism.

Āyāro: Supra-logical reality

let us look at the following statement of the Āyāro:

“All words come back (from that)

Logic doesn’t reach there

Contemplation cannot grab it

It is neither big nor small

Neither circular nor triangular”

And the description goes on - it has no colour, no smell, no taste, no touch, no birth, noattachment, no sex etc[1].

The Upaniṣads

Now this is easily comparable to the upaniṣadic statements like from where the words come back along with mind[2] or ‘the wise speak of it as not-gross, not-atomic, not-small not-big[3]’ or ‘without word, without touch, without form[4].’ Here we have the connecting link between the Upaniṣads and the Jaina tradition. With such similarity can we say that Jainism arose as a revolt against Brahamanism? Or instead of saying that Upaniṣdic thought influenced Jainism or vice versa, will it not be nearer the truth that all spiritual aspirants have similar experience?

Samayasāra: Continuity of the tradition

In fact, Samayasāra of Ācāraya Kundakunda continued the tradition when and said that “Pure Self is without taste, colour, without smell, imperceptible to touch, without sound, not an object of anumĀna or inferential knowledge, without any definite bodily shape and is characterized by consciousness.[5]

Revolution: Beyond rituals

This was a continuation of the upaniṣadic tradition through Āyāro. But more revolutionary was the idea of condemning even such practices as pratikramaṇa:

“Repentance for past misconduct, pursuit of the good, rejecting the evil, concentration abstinence from attachment to external objects. Self-censure, confessing before the master, purification by expiation - those eight kinds constitute the pot of poison.[6]

Not only that, the absence of all these are said to be pot of nectar[7]. This type of revolutionary attitude naturally led to making Ācārya Kundakunda a figure around whom controversies arose in different forms.

Supra-moral plan:

One such controversy is regarding whether Ācārya Kundakunda has obliterated distinction between good and bad. In fact, he stands apart in propagating a supra-moral plan of ethics, which is again a continuation of the Upaniṣadic tradition where ultimate reality is said to be beyond good and bad. We have elaborated this point elsewhere how the idea of transcendental morality is universal in Indian thought and Ācārya Kundakunda is the pioneer in the field of Jainism in this respect.[8]

Ācārya Bhikṣu and Jaina Agamas:

Coming to Ācārya Bhikṣu, we again find a new turn in Jaina History of philosophy. Let us think of the following statement of Sūtrakṛtāṅga:

There are institutions, which offer food and gifts to the needy. One should neither recommend such act of aims giving by declaring them to the meritorious nor should one condemn them by declaring them to be non-meritorious. If one recommends them, he approves of the violence involved in such activities; if one disapproves them he deprives the beneficiary of the means of his subsistence. One should, therefore, make statement neither way. This is the way of emancipation.[9]

This is the Āgamic basis of the concept of Ahimsa as pounded by Ācārya Bhikṣu (birth 1726 A.D.) where views led him to break away from Sthānakvāsī sect. The above quoted portion of Sūtrakṛtāṅga prohibits declaring meritorious or non-meritorious any act of alms giving to the needy, Ācārya Bhikṣu concluded that what is commonly taken to be meritorious is really not so according to Jain Āgamas. His line of approach is, in short, as follows:

- in the first place, the path of liberation is diametrically apposed to the path of worldly life. You cannot expect to follow both simultaneously. The worldly pleasures belong to senses whereas the bliss of liberation is super-sensuous. The sensual pleasures are, therefore, obstacles in the path of liberation. This is accepted by all who aim at liberation.

- All help which is rendered for the augmentation of worldly pleasures is due to attachment is not a part of non-violence. If one forgoes worldly pleasures for oneself, how can he think of providing worldly pleasures for others?

- As far as the help to be rendered to those who are deprived is concerned, one should appose exploitation and support establishment of a society free from poverty, in equality and injustice. Giving aims to the poor does not eradicate poverty.

- Money is not the means to dharma. If it were so, the Thīrtaṅkaras would not have abandoned their kingdom; they would have acquired merit by using their means for social welfare.

- Heaven is not the aim of dharma. Heaven is, in fact, an extension of the worldly pleasures in life hereafter. The aim is liberation from worldly life, and therefore, from all worldly pleasures also. How can one promote worldly pleasures in any form?

- Worldly pleasures are dependent on external circumstances and are, therefore, temporary. The bliss of the self is independent of any external help and is, therefore, permanent.

- Worldly pleasures belong to body, senses and mind. They find one existence. Non-possessiveness is, therefore, the aim of spiritual life. One should practice it oneself and promote it for others also.

- Non-violence is the absence of attachment. Normally we think that aversion or enmity is to be avoided. In fact what we commonly consider to be friendship is based on give-and-take of selfishness. True friendship lies in helping others in pursuing the path of liberation.

- Serving or helping others involves two major questions: (i) will our help promote spiritualism or materialism? (ii) while helping one, are we not depriving the others of his rights? It means that only one who deserves our help spiritually should he helped and the means of rendering such help should be non-violent. We don’t consider it a good thing to help a thief in escaping from the Police. How can we think of helping a person who is involved in violence, to be a meritorious action?

- Helping others by providing them food etc. could be a part of social duty but it cannot be a part of spiritualism.

- Non-violence involves (i) freedom from anger, greed, hypocrisy, ego, hatred, fear etc as far as the self is concerned and (ii) freedom from exploitation, torturing, inflicting, insult etc. is the social aspect of non-violence.

- The real help is to help others in following the path of liberation.

- The purpose of life is of observance of self-control. When on saves anybody from the tyranny of the other, the major merit lies in changing the heart of the tyrant and not in saving the victim of the tyranny.

- We are under obligation of the society - our parents, our teachers and all those who help us in any way. It is our duty to help them in return. But what kind of help can we render? If it is material help, then we need money to help them. It could be a necessity but it cannot be a part of spiritualism, which has no relationship with possessiveness.

- The two, therefore, should be separated - the spiritualism and the social obligation. The spiritualism doesn’t change but the social order changes from time to time. If we intermingle the two, either the social order becomes stagnant and static like spiritual order or the spiritual order too becomes volatile like the social order. Take for example the institution of monarchy, which has been replaced by democracy in most of the countries. Now if we hold that king is a divine entity, then discarding monarchy would be a sin against divinity. But if we hold monarchy or democracy as secular, we can replace them by a better order without committing any sin.

- As regards the duty of a householder, he has to reduce the amount of violence to the maximum while discharging his social obligations.

- As regards social or political order, it is clear that old order changed yielding place to new. Let not spiritualism become an obstacle in the way of dynamic nature of society. Manusmṛti, for example, could have been relevant in the past but to-day we have to adjust to modern times, otherwise we would leg behind the time. On the other hand, we should not compromise in the field of eternal values in the name of progress.

- Jainism as such has been secular in the sense that it has not tried to impose any secular code on the non-Jainas. It has rather asked the Jainas to follow the common civil code provided that it doesn’t hinder the right attitude and observation of vows:

सर्व एव हि जैनानां प्रमाणं लौकिको विधिः

यत्र न सज़्यक्त्वहानिर्यत्र न व्रतदूषणम्।Thus whereas Ācārya Kundakunda and his commentators Amṛtacandra came to the conclusion that the essence of non-violence is detachment, Ācārya Bhikṣu added that non-violence means change of heart and not imposition of any rule by force and that material help could be part of social obligations but is not a part of spiritual non-violence.

The Futuristic Turn

Modern time have seen much more turning points than at any given time of history because of epoch-making researches in the field of science. These researches are likely to affect the philosophy also. Some of such researches have supported the Jaina concept in a unique way.

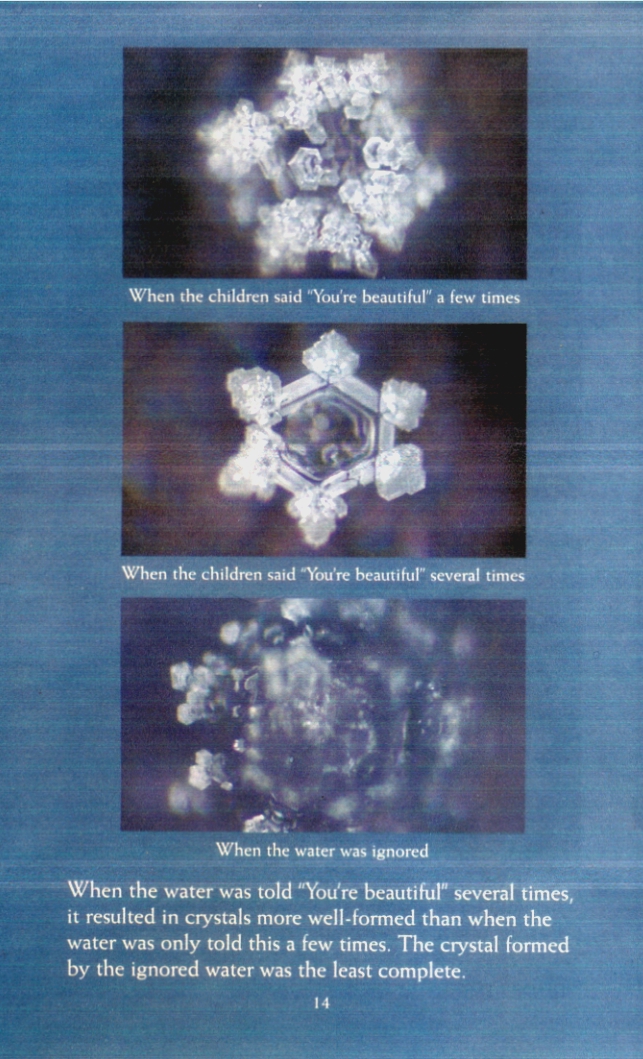

Take for example, the concept that earth, air, water and fire also have life. Now a Japanese scholar Shri Masaru Emoto in his recent book, the hidden message in water (New York, 2004) has shown through high speed photograph, how water responds in clear terms through crystals to our positive attitudes of love, gratitude and thankfulness on one hand and to our negative attitude like hatred and violence on the other. We can see this in the form of photographs produced below how the water showed well-formed crystal when told ‘you are beautiful’ several times and only a few times, whereas the crystal was least complete when the water was ignored.

Also attention may be drawn to the following Editorial of Times of India of December, 2005, which puts a challenge to the Jaina theory of non-absolutism.

“As far as common sense is concerned quantum mechanical theory is not just counter intuitive, it’s way beyond weired... yet now, uncanny as it seems, a team of scientists lead by Professor Dietrich Leibfried of the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Colorado, USA has succeeded is producing up to a half dozen atoms of the element beryllium which can be said to be spinning simultaneously in two different directions. That’s like saying something can be going up and down, left or right or even back or forth at the same time. And they are not alone. A similar experiment conducted by Australian researchers has also been published in a recent issue of journal science.”Here is a discovery, which should make Jaina thinkers to re-interpret the theory of non-absolutism. It is a case of bizarre behaviors of matter, which was hitherto unknown to us. Jainācāryas have been speaking of contradictory characteristics of existence like change-cum-continuity in the same object (and of, in fact, in all objects). But here is another puzzle. Can an atom behave in the way in which has been described above? Or have we reached the same place from where we started in the Āyāro:

All words come back (from that).

Logic does not reach there.

Contemplation cannot grasp it.

Prof. Dr. D.N. Bhargava

Prof. Dr. D.N. Bhargava