Centre of Jaina Studies Newsletter: SOAS - University of London

This report summarizes the findings of my PhD dissertation, Health, Well-being, and the Ascetic Ideal: Modern Yoga in the Jain Terāpanth, which I completed in the Department of Religious Studies at Rice University in April 2010. The dissertation evaluates prekṣā dhyāna, a Terāpanthī school of yoga. I found that the practice and ideology of prekṣā dhyāna (henceforth prekṣā) are context specific. In the monastic context, it functions as a metaphysical, mystical, and ascetic practice. In this way, it aims at purification and release of the soul from the world. In its popular dissemination, it functions as a physiotherapeutic practice for the sake of physical and psychological benefits. In this context, it is a case study of modern yoga, which aims at the enhancement of life in the world. I am primarily concerned with prekṣā as a case study of modern yoga.

By modern yoga, I refer to schools of yoga that began to emerge in the nineteenth century and developed as a consequence of encounters between European and American metaphysicians and participants in physical culture (such as gymnastics and calisthenics), Indian yoga gurus, and modernity. Since the second half of the twentieth century, modern yoga has been popularized. Proponents market it as a system of body practices, particularly āsana, aimed at physical health as well as stress reduction and thus the enhancement of life.

Such qualities and aims seem contrary to the worldrejecting ascetic ideal associated with the Terāpanth. Bhikṣu (1726-1803), the founder and first ācārya, was a Śvetāmbara reformer who left his order in 1759. He established a new order, the Terāpanth, in 1760 and asserted that it returned to Mahāvīra's dualist ontology, which has its logical end in an ascetic ideal that requires the reduction and eventual elimination of all physical and social action. He maintained that ahiṃsā is about the purification of the soul in its quest toward release from the body. Bhikṣu thus distinguished between two realms of value. The worldly realm consists of any action directed toward worldly benefits. The spiritual realm includes behavior oriented around ascetic purification. Bhikṣu argued that only spiritual behavior was appropriate for Jain monastics.

The contemporary Terāpanth is largely a product of innovations during the leadership of the ninth ācārya, Tulsī (1914-1997). Tulsī believed that Mahāvīra practiced a Jain form of yoga that was gradually lost, and he wanted one of his disciples, Muni Nathmal (1920-2010), to rediscover this system by means of research on Jain literature and personal experimentation. In 1975, Nathmal introduced prekṣā dhyāna, literally, 'concentration of perception', but most often translated by the tradition as 'insight meditation and yoga'.[1] He presented prekṣā as universal and scientific. When he was selected by Ācārya Tulsī as his successor, his name was changed to Mahāprajña or 'Great Wisdom'. Mahāprajña was consecrated as the tenth ācārya in 1994 and continued in that role until his recent death on 9 May 2010.

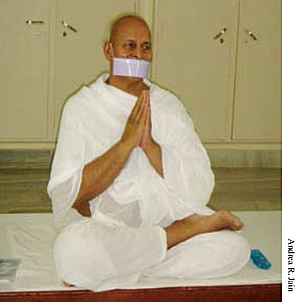

Terāpanth Muni (Lāḍnūn, Rājasthān)

On the one hand, the introduction of prekṣā was not socioculturally innovative but was consistent with other social trends at the time: first, the popularization of Satya Narayan Goenka's vipassanā ('insight meditation' prescribed as a 'universal' form of Buddhist meditation) within and beyond India; second, the turn by Indian yogis, often motivated by nationalism, to yoga as a tool for enhancing the male physique; and third, the global popularization of yoga as a practice for the enhancement of life, especially in India, the United States, and Europe.

On the other hand, prekṣā was a radical religious innovation because, in its popular dissemination, proponents embraced the worldly aims of health and well-being. Spiritual practice was not about the ascetic ideal but āsana and prāṇāyāma as fitness techniques. Furthermore, by appropriating the physiological and anatomical discourses of biomedicine, proponents of prekṣā medicalized a system that was classically a metaphysical practice aimed at purification, the manipulation of subtle energies, and mystical experience.[2] In these ways, it is a case study of modern yoga.

The Terāpanth prescribed prekṣā for all lay people concerned with the enhancement of life. This led to an additional innovation on the part of the Terāpanth, since representatives were needed to teach prekṣā to people throughout India and the world. Thus, beginning in 1980, Tulsī introduced a new order of monastics, the samaṇas, who live a life of renunciation, but are not fully-initiated monastics. Although in 1986, four male samaṇs were initiated, the large majority are samaṇīs or female samaṇs.[3]

Samaṇīs gather in preparation for Mahāprajña's birthday celebration (Lāḍnūn, Rājasthān, June 2009).

What makes this order innovative is the fact that the rules governing it are more lax than those for fullyinitiated monastics. This enables the samaṇīs to travel throughout India and abroad in order to bring about the global dissemination of prekṣā. The existence of this order makes it possible for the Terāpanth to maintain a world-rejecting ascetic ideal while sustaining participation (through the intermediary role of the samaṇīs) in worldly affairs.

In order to explain why such innovations occurred, I evaluated their relationship to sociocultural context. I found that prekṣā intersects with the culture of late capitalism, insofar as its proponents participate in the modern yoga market. By 'late capitalism' I refer to the decentralized consumerism that began in the second half of the twentieth century when technological and economic processes brought about the pluralization of transnational commodities. I am concerned with the cultural consequences of such processes, and thus I use capitalism and consumerism as categories for cultural critique rather than for an analysis of economic exchange. I am concerned with the cultural qualities of late capitalism, which include religious pluralism as well as processes whereby individuals choose religious identities and practices in response to individual desires and needs. In this sense, choosing religious identities and practices became akin to choosing commodities.

The Terāpanth participates in this culture by marketing prekṣā in response to popular demands for body practices aimed at health and stress reduction. This strategy requires that prekṣā be compatible with certain dominant metaphysical and scientific paradigms of late capitalist culture, particularly biomedicine and the conception of the body as a part of the self to be developed and enhanced. In their strategies to achieve compatibility with those cultural paradigms, proponents of prekṣā emphasize its physiological function and consequent benefits to a life lived well.

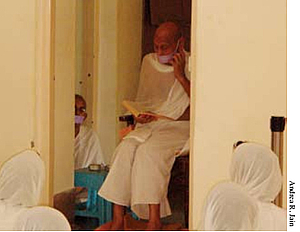

A group of samaṇīs sitting with Mahāprajña (Lāḍnūn, Rājasthān, July 2009).

The Terāpanth, however, does not cease to privilege the ascetic path. Thus proponents adopt a dual-ideal whereby the practitioner is called to engage with the body as a potential tool for achieving health and well-being, but if one desires advanced spiritual progress, then one must realize the truth of Jain soteriology and enter onto the ascetic path. That path necessitates full initiation into the monastic order.

I conclude with some thoughts on the successes and failures in the global dissemination of prekṣā. Proponents have succeeded in participating in the modern yoga market by constructing and disseminating prekṣā as a yoga system for the enhancement of life. However, they have failed to attract students in large numbers and rarely appeal to modern yoga practitioners beyond Jain and Hindu communities. I argue that it is because of the dual-ideal between the enhancement of life and the renunciation of life, that prekṣā does not have large-scale appeal in the modern yoga market. The samaṇīs teach prekṣā as a life-affirmative practice, but their devotion to the ācārya reminds students that a world-rejecting asceticism is privileged as the path to advanced spiritual development. Prekṣā is believed to enhance health and well-being, but those are means to the advanced goal of purification. In the culture of late capitalism, modern yoga is popular as a path to a life lived well, and that goal is not a means but an end in itself.

Andrea R. Jain is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Andrea's primary areas of research and teaching are South Asian religions and the social-scientific study of religion, with a focus on religion and the body. Andrea's current projects include studies on the intersection of consumer culture and modern yoga as well as the role of food practices and guru figures in modern yoga traditions.

Members of the Terāpanth most often translate the full title of prekṣā dhyāna as "prekṣā meditation," but since the category of "yoga" includes dhyāna or "meditation," and prekṣā involves more than just the meditative components of yoga, I use "yoga" in the current essay.

For a study of this phenomenon in modern yoga in India, see Alter, Joseph S. Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Ph.D. Andrea R. Jain

Ph.D. Andrea R. Jain