Modern science and technology have brought high standards of material comfort and welfare to people, particularly in the 'developed' countries. However, these material gains have not brought satisfaction or contentment. On the contrary, they seem to have created more greed, conflict, insecurity, unhappiness, anxiety, stress and illness. In the face of the failure of wealth and material comforts to deliver contentment, many are turning to yoga and meditation, an age-old tradition, to regain their physical and mental health.

Yoga was a way of life in ancient India. The word yoga is from the ancient Sanskrit, from yuj meaning 'join'. By extension, it carries the figurative sense of 'concentration', religious or abstract contemplation. Yoga is a spiritual activity of mind, body, or speech aimed at achieving liberation or self-realisation. In theistic philosophies, its aim is to merge with the Supreme Being. The concentration of the mind onto a particular object is generally termed 'meditation'. Through the continual practice of yoga and meditation, the spiritual aspirant can achieve the goals of mental peace, inner happiness, and the annihilation of karmic bondage, leading to self-realisation and enlightenment.

Mahavira's life is a superb example of the yogic path. The foundation of Mahavira's spiritual practice was meditation combined with yogic postures, leading to bodily detachment. This combined activity is known as kaayotsarga. Austerities, such as fasting and yogic postures, inspired and complemented his spiritual practices, which were not a special ritual, but an essential part of his life. For example, he always observed silence and carefully followed his chosen path, living totally in the present. Whatever he did, he was totally engrossed in it without either any impression of the past or imagination of the future. He was so much absorbed in meditation (kaayotsarga), that he did not experience hunger, thirst, heat or cold. His mind, intellect, senses, all his concerns, moved in one direction: towards the 'self' and self-realisation, and emancipation.

The aim of all spiritual practices is to achieve control over one's activities (yogas): mind, body and speech. All ethics and external austerities are means to achieve concentrated deep meditation. Meditation was very commonplace in both Jain ascetics and laypersons up to the first century BCE. The practice of meditation gradually became secondary, leaving few Jain exponents of the meditation techniques of Mahavira. Later, other ethical and ritual practices, and external austerities displaced it.

The Buddhist scripture Tripitakas asserts that the Buddha practised meditation through being initiated in niggantha dhamma, that is Jainism (Jain B 1975: p.163). The small image of Parsvanatha on the head of the great statue of Buddha in the Ajanta caves (seventh century CE) suggests that Buddha was meditating on a symbol of Parsvanatha, and the later Chinese and Japanese forms of Buddhist meditation such as Zen Buddhism may have their roots in the spirit of Jain meditation. In the Dhammapada the Buddha has stated that those in whom wisdom and meditation meet are close to salvation (Bhargava 1968: p.193). Patanjali (second century BCE) argues in the Yoga Sutra, that meditation is the vehicle that gradually liberates the soul and leads to salvation (Bhargava 1968: p.193). The practice of meditation differs from one system to another, but all agree regarding the importance of meditation for spiritual progress.

Williams (1963) describes Jain Yoga as spiritual practices, such as vows, 'model stages', rituals and the worship of householders and ascetics. It is to the credit of the Jain seers that they integrated yoga, meditation and other spiritual practices into the daily routine of both laity and ascetics. When the duties of equanimity (saamayika), penitence (pratikramana) and the regular veneration of images (pujaa, caitya vandana) are practised as part of daily life, attending special yoga and meditation classes, so popular in the modern age, becomes unnecessary.

In recent centuries, yoga and meditation have become widespread as part of the daily practices of both Jain ascetics and laypersons. This has happened through the efforts of great 'yogis' (mahaayogi) such as Anandaghana (seventeenth century), Buddhi Sagara and Srimad Rajchandra (late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries) Bhadrankarvijay, Sahajananda and Mahaprajna (twentieth century).

Yoga

The religious and spiritual path, which leads towards liberation, is known as yoga and all Jain ascetics and lay aspirants practise this noble path. The Aacaaranga, Tattvartha Sutra and other scriptures have described this path both for ascetics and for laypersons, but it was Haribhadra (eighth century CE), Subhacandra (tenth century CE) and Hemcandra (eleventh century CE) who gave detailed expositions on yoga. In his book, Yogavinshika, Haribhadra describes five types of yoga:

- The yoga of postures: such as padmaasana, siddhaasana, veeraasana, and kaayotsarga

- The yoga of spoken words in the religious activities and rituals

- The yoga of the meaning of these utterances

- The yoga of meditation on objects such as images of tirthankaras, siddhas, ascetics

- The yoga of deep meditation on the soul (Sukhlal 1991: p.65)

Of these five, the first two are physical activities (karma yoga or kriyas) and the last three are 'knowledge activity' (jnaana yoga). Postures such as the posture of 'five limb bowing' (khamaasana), the posture of 'two palms together touching the forehead' (muktaa sukti mudraa), the posture of the 'Jina-modelled sitting or standing' (jina mudraa), the posture of 'detached body' (kaayotsarga mudraa), and yogic postures such as padmaasana and veeraasana are important in Jain rituals. Jain rituals are required to be carried out with the correct postures and precise pronunciation of the utterances if one is to achieve maximum benefit.

Jnaana yoga requires that one understand the meaning of what one reads or says. To enable the mind to concentrate, Jain experience has found the aid of the images or their symbolic representation to be useful. Love, devotion, sentiments and the sounds which one utters, all play a role in yoga. Continuous practice is necessary for progress on the path of liberation, and all spiritual activities and rituals should be performed conscientiously.

Haribhadra wrote extensively on yoga in his Dharmabindu and Yogabindu. In another important work, Dhyanasataka, he describes meditation in considerable detail. Hemcandra's Yoga Sastra is the most significant work on religious practices based upon the principles of Right Faith, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct; it describes the corpus of rules, which regulate the daily life of laypersons and ascetic life. Similarly, Somadeva's Yashastilaka describes the ritual activities marking the stages of progress in both lay and ascetic life. Many ascetics have written on yoga and meditation: important later works include Jnaanarnava by Subhacandra, Dhyanadipika by Sakalacandra, and Preksaa Dhyaana by Mahaprajna.

Jain meditation

The Tattvartha Sutra defines meditation (dhyaana) as concentration on a particular object. Such intense concentration is sustainable only for a limited period, the Tattvartha Sutra (1974: 9.27) states that the limit is forty-eight minutes (antar muhurta). After this, perhaps after a momentary pause, one may resume meditation, focussing on the same or a different object, but to an outside observer, the meditation may appear to be unbroken.

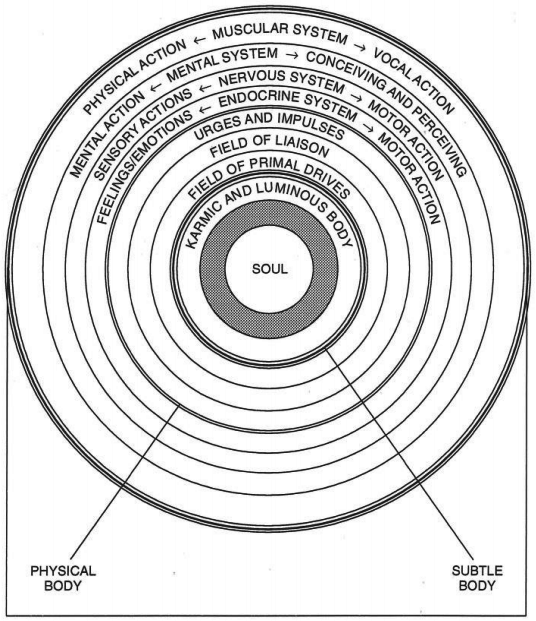

Before we go on to discuss the types of meditation, their requirements and their role in spiritual development, it is essential to understand the Jain view of the structure of a living organism and the effect of yoga and meditation on its functioning.

A living organism is a unity comprising of two elements - a non-material conscious element, which we might term the 'psyche' or 'soul', and a material element, which we can call the body. The constituents of the living organism are the body; the sensory organs and the brain; a subtle luminous body; a more subtle karmic body; the sub-conscious mind (citta); the primal drive (adhyavasaaya); and finally, the psyche or the soul.

The soul itself, a conscious entity, forms the nucleus of the organism. A contaminating field producing malevolence (the passions), derived from the karmic body, envelops it; this field not only circumscribes but also governs psychic activity. Transcendentally, the soul is the supreme 'ruler' but, in actuality, the influence of the passions is so powerful that the ruler is unable to act independently. The soul radiates psychic energy, but the radiations have to pass through the domain of the passions. During their passage, they interact with the passions and form a new field; in Jain scriptures this is the 'domain of the primal drive' i.e. the primal psychic expression. Further, the radiation intermingles with the other subtle bodies, luminous and karmic, and the consequences are biochemical and bioelectrical. While the mental states due to cerebral activity are not found in all living organisms, but only in vertebrates, the primal drive is present in every living organism, including plants. These animate expressions of the subtle body are the progenitors of mental, vocal and physical activity, manifested in the physical body. Proceeding towards the physical body, these expressions pass through the domain of the psychic aura, intermingle with it, and are converted into urges and impulses. These are the forerunners of emotions, passions and feelings, manifested in the physical body. The aura is produced by the transcendental force of the effects of past actions, which are fully recorded in the karmic body. Empirically, the aura may be conceived of as a liaison between the past and the present careers of the soul as well as between the subtle and the physical or gross body.

The radiations of urges and impulses move between the subtle body and the gross body. These compelling drives, derived from the subtle body, activate the endocrine system when they reach the physical body, stimulating the latter to secrete and distribute chemical messengers (hormones) corresponding to the nature and intensity of the impulse. Thus the hormones become the agents for executing the primal drives in the physical body.

Figure 4.14 The relationship between the subtle and the physical body

Figure 4.15 The Jain view of the relationship of the body to behaviour

The chemical messengers secreted by the endocrine glands are carried by the bloodstream and interact with the brain and the nervous system; together they constitute an integral co-ordinating system, which modern medicine calls the neuro-endocrine system. This system not only controls and regulates every bodily function but also profoundly influences mental states, emotions, thought, speech and behavioural patterns. Thus, the endocrine glands act as transformers between the most subtle spiritual 'self' and the gross body. They are gross when compared with the domain of the primal drive, but subtle when compared with the gross constituents: muscles, blood and other bodily organs. This, then, is the inter-communicating mechanism within the body, which translates the intangible and imperceptible code of the primal drive into forms crude enough to function through flesh and bones.

The pure soul radiates its characteristic infinite bliss, knowledge, perception and energy. The impure soul's radiation becomes distorted, as it must pass through the cloud of karmic body and the malevolent field of passions, it produces primal drives.

The primal drives depend upon the karmic components and create the psychic mind (conscious mind) with a distorted knowledge and perception, and the psychic mind radiates distorted images across the field of liaison between the subtle and the gross bodies.

The physical mind acts as a vehicle for the flow of emotions, which stimulates the endocrine and nervous systems, creating thought, speech and bodily activities.

Aura and lesyaas

The aura of a living organism is an amalgam of two energies: the vital energy of consciousness and the electro-magnetic energy of the material body. Mental states constitute the compelling force produced by the radiation of vital energy. Jain scriptures describe how this vital energy is responsible in effecting the physical brain and releasing the electo-magnetic material particles to produce an aura of the person. If the mental state is pure, the aura is gratifying and if the mental state is impure and full of the passions, the aura is repulsive. The aura of the saints is gratifying and is often shown as a halo around their heads. Although mental states are conscious and aura is material, there is an intimate relationship between the two. Aura is the image of mental states of an individual.

Lesyaas: Jain scriptures have described lesyaas, which are inadequately translated as psychic 'colours', and their functions. They act as a liaison between the spiritual 'self' and the physical body of a living organism. They are the built-in mechanism within the organism through which the spiritual self can exercise its power, and control the functioning of the bodily organs. Psychic 'coloration' functions in both directions, centripetal, from periphery to the centre, and centrifugal, from centre to periphery. Karmic material is continually attracted from the external environment by the threefold activities of the physical body: thought, speech and action, and this material is transferred into the sphere of the passions in a subtle form. Similarly, whatever is radiated outwards from the subtle karmic body at the centre, is transferred to the gross body by the psychic colours.

'Colorations': The 'malevolent' (asubha) colorations are black, blue and grey and are the origin of evil. Cruelty, the desire to kill, the desire to lie, fraud, deceit, cheating, lust, dereliction of duties, laziness and other vices, are produced by these colorations. The endocrine glands, the adrenal gland and the gonads, work in close alliance with these colorations to produce impulses, which in turn, stimulate the body through endocrine action, expressing themselves in the form of emotion and passion.

The 'benevolent' (subha) colorations are yellow, red and white and are the origin of good. Perception of these bright colours curbs evil drives and transmutes the emotional state of an individual. Evil thoughts are replaced by good; thus internal purification of the mental state radiates beneficial waves to influence the external environment.

How meditation works

Relaxation and bodily detachment are the prerequisites of meditation. Meditation is the process by which one searches for the cause of misery and suffering; the gross body is the medium for the perception of suffering and its manifestation, but it is not itself the root cause. The root cause is the subtle karmic body that deludes, so that the spiritual 'self' remains unaware of its own existence. The karmic body produces vibrations, shock waves in the form of primal drives, urges and impulses, and influences the activities of the gross body, mind and speech. When all bodily activities are halted through bodily detachment, mental equilibrium is arrived at through meditation, and the vibrations, primal drives, urges and impulses become ineffective, thus meditation calms the waves produced by primal drives.

The karmic body continues transmitting vibrations and sheds karmic particles, and the true characteristics of the soul, bliss, energy, faith and knowledge appear. Thus meditation aids the soul in shedding the karmic body and achieving self-conquest. This is shown in figure 4.16

Diagram 4.16 Meditation and its effects

Meditation is the acquisition of maximal mental steadiness. Unless the body is stable, the mind cannot be still. The muscular system is the basis of bodily activity; relaxation and bodily detachment help achieve this stillness of mind.

The first step in a meditation exercise is to adopt an appropriate posture, and then remain motionless for some time. Control of one's breathing, concentration on psychic and energy centres and the psychic colours, together with contemplation and autosuggestion aid meditation.

Types of Meditation

Jain scriptures describe four forms of meditation: 'sorrowful' (aarta) 'cruel' (raudra), 'virtuous' (dharma), and 'pure' (sukla); the first two are inauspicious and the last are auspicious.

Sorrowful meditation (aarta dhyaana): Sorrowful meditation has been further classified under four sub-types:

- contact with undesirable and unpleasant things and people;

- separation from desired things and loved ones;

- anxiety about health and illness;

- hankering for sensual pleasures.

Sorrowful meditation, though agreeable in the beginning, yields unfortunate results in the end. From the point of view of colorations it is the result of the three inauspicious psychic colours. It requires no effort but proceeds spontaneously from the previous karmic impressions. Its signs are: doubt, sorrow, fear, negligence, argumentativeness, confusion, intoxication, eagerness for mundane pleasures, sleep, fatigue, hysterical behaviour, complaints, using gestures or words to attract sympathy, and fainting. Sorrowful meditation is due to attraction, aversion and infatuation and intensifies the transmigration of the soul. It is associated with 'malevolent' psychic colours. Usually people who engage in this form of meditation are reborn as animals, and it lasts up to the sixth spiritual stage.

Cruel Meditation (raudra dhyaana): This meditation is more detrimental than sorrowful meditation and is classified into four sub-types

- harbouring thoughts of violence,

- falsehood,

- theft,

- 'psychopathic' guarding of material possessions and people.

The first sub-type called 'pleasurable violence' means taking delight in killing or destroying living beings oneself or through others. It includes taking pleasure in violent skills, encouraging sinful activities, and association with evil people. This cruel meditation includes the desire to kill; taking delight in hearing, seeing or recalling the miseries of sentient beings and being envious of other people's prosperity.

The second sub-type is 'pleasurable falsehood'. It means taking pleasure in using deception, deceiving the simple-minded through lies, spoken or written, and amassing wealth by deceit.

The third is 'pleasurable theft'. This form of meditation includes not only stealing but also encouraging others to steal.

The fourth is 'pleasurable guarding' of wealth and property. It includes the desire to take possession of all the benefits of the world and thoughts of violence in attaining the objects of enjoyment. It also includes fear of losing and violent desires to protect possessions.

It is obvious that only someone who is fully disciplined can avoid cruel meditation. Pujyapada has pointed out that the cruel meditation of a righteous person is less intense and cannot lead to infernal existence (Sarvarthasiddhi 1960: 9.35). Cruel meditation lasts up to the fifth spiritual stage.

Sometimes this meditation occurs even to ascetics on account of the force of previously accumulated karma. It is characterised by cruelty, harshness, deceit, hardheartedness and mercilessness. The external signs of this meditation are red eyes, curved eyebrows, fearful appearance, shivering of the body and sweating. Those involved in such a meditation are full of desires, hatred and infatuation, and are usually reborn as infernal beings. This meditation is associated with three intense 'malevolent' psychic colours.

Virtuous Meditation (dharma dhyaana): Inauspicious meditation happens spontaneously, without effort. Auspicious meditation, virtuous and pure meditation, which leads to liberation, requires effort. Jain scriptures advise keeping the mind occupied with simple mantras such as namo arham, meaning honour to the worthy, so that one does not succumb to inauspicious meditation. Auspicious meditation helps to control desires, hatred and infatuation. The object of this meditation is to purify the soul.

Requirements for virtuous meditation: Whether accompanied or alone, anywhere to an appropriate place fit for meditation, if the mind is resolute. But surroundings influence the mind and places where disturbances occur should be avoided. Places that are sanctified by its association with great personages are peaceful, such as certain temples, the seashore, a forest, a mountain, or an island should be chosen. Preferably a place for meditation should be free from the disturbance due to noise or the weather. The householder can also choose a quiet corner of the home for regular meditation.

Any meditation posture is suitable for the detached, steadfast and pure person, yet postures are important. Subhacandra mentions seven postures: padmaasana, ardhapadmaasana, vajraasana, viraasana, sukhaasana, kamalaasana, and kaayotsarga. The first two, the lotus and half-lotus positions, and the last of these seven, standing or sitting meditation are particularly suitable for our times.

As Patanjala yoga, a famous Indian system, gives great importance to 'spiritual breathing' (pranaayama), Jainism also attaches importance to the control of breathing as an aid to control the mind. If performed correctly, it helps to develop certain energies and the practitioner may even develop supernatural powers, but pranaayama performed without the objective of controlling the mind may lead to sorrowful meditation.

Conscious control over the senses is essential in controlling the mind, as when the sensory organs become attenuated, they interact with the mind in a harmonious way. One can concentrate on such areas as the eyes, the ears, the tip of the nose, the mouth, the navel, the head, the heart and the point between the eyebrows.

The object of virtuous meditation: Amongst the objects upon which one can meditate are: the sentient and the insentient; their triple nature of existence, birth and destruction; a worthy personage (arhat) and the liberated one (siddha). One should learn to distinguish between the 'self' and the body. The self has neither friend nor foe; it is itself the object of worship and meditation and possesses infinite energy, knowledge, faith and bliss. The body, which may have physical beauty, strength, attractions, aversions, material happiness, misery and longevity, is temporary in nature due to the effects of the karmic body.

Types of virtuous meditation: Jain scriptures describe four types of virtuous meditation: reflection on the teachings of the Jinas (aajnaa vicaya); reflection on dissolution of the passions (apaaya vicaya); reflection on karmic consequences (vipāka vicaya); and reflection on the universe (sansthaana vicaya) (Tattvartha Sutra 1974: 9.36)

- Reflection on teachings of the jinas: This meditation involves having complete faith in the nature of things as taught by the omniscients and recorded in the scriptures. When the mind is fully occupied in the study of the scriptures, it constitutes this meditation.

- Reflections on dissolution of the passions: This meditation involves deep thinking on the effects of the passions (anger, pride, deceit, greed) and attractions and aversions, and their adverse effects that harm the soul and counter the spiritual path. A thoroughgoing consideration of the means of overcoming wrong belief, wrong knowledge and wrong conduct constitutes this meditation.

- Reflection on karmic consequences means thinking of the effects of karma on living beings. All pleasure and pain is the consequence of one's own actions, which should be regulated and controlled. This meditation is aimed at understanding the causes and consequences of karma.

- 'Reflection on the universe' is meditating on the nature and form of the universe with a view to attaining detachment. It includes reflection on the shape of the universe: the lower region with its seven infernal regions and their miseries, the middle region which contains human beings, and from which one can achieve liberation, and the upper region of the heavens with their many pleasures but from which liberation is not possible, and at the very apex the abode of the liberated. The meditation of 'reflection on the universe' is of four sub-types:

- Reflection on the Body (pindastha): This is meditation on the nature of the living organism and the destruction of the main eight types of karma, the purified self and the attributes of the liberated.

- Reflection on Words (padastha): This is meditation on the syllables of certain incantations such as the Namokara and other mantras made up of differing syllables, and their recitations; the repetition of these mantras may lead to the attainment of supernatural powers.

- Reflection on 'Forms' (rupastha): This meditation concentrates on the different 'forms' which worthy personages may take in their worldly life (e.g. such individuals may be rulers, ascetics, omniscients, preachers). It may also focus on any material object or on the image of a tirthankara and the spiritual qualities of the enlightened, and it leads to the realisation of the ideal on which one meditates.

- Reflection on the 'Formless' (rupaatita): Meditation on form implies reflection on embodied liberated souls, i.e. the enlightened ones, whereas meditation on the 'formless' implies reflection on disembodied liberated souls; ultimately this is a meditation upon one's own pure soul and it leads to self-realisation.

Supervision from a qualified teacher, constant practice and perseverance are needed to master virtuous meditation.

The benefits of virtuous meditation: The first signs that one is benefiting from this form of meditation are control over the senses, fine health, kindness, an auspicious aura, bliss and clarity of voice. It leads directly to heavenly pleasures and indirectly to liberation through merit, stopping the influx of karma and the shedding of previously acquired karma. This meditation is associated with three auspicious psychic colours. Individuals engaging in this type of meditation are reborn either as heavenly or as human beings. This virtuous meditation lasts up to the thirteenth spiritual stage.

Pure meditation (sukla dhyaana): In virtuous meditation consciousness of the distinction between the subject and the object of knowledge persists; whereas in pure meditation all conceptual thinking gradually ceases, and pure meditation emerges when the passions have been destroyed.

Only someone with an ideal type of constitution and full knowledge of the scriptures can engage in pure meditation, but it is believed that in the modern age such people no longer exist on this earth. Hence the notion of pure meditation is only of academic interest. Pure meditation is the final stage before liberation and is associated with the auspicious white psychic colour.

As meditation is prominent in the teachings of eastern philosophies, we describe below the meditation in Hinduism and Buddhism.

Meditation in Hinduism and Buddhism

Yoga and meditation form an essential part of the spiritual life of Hindus. The Bhagavad Gita claims activity that frees the soul from attachment and aversion is yoga (Bhagavad Gita 1978: 6.4). Patanjali defines yoga as the path of self-realisation through control of one's desires and control of one's mind, by physical or psychic means. He emphasises the importance of the eightfold path in realising perfect meditation resulting in the soul's union with the supreme being; this includes mortification, the singing of certain hymns, and a devoted reliance on the 'Supreme Soul', God. The following eight paths are prescribed by Patanjali for a true yogi: self-control (yama), observance (niyama), posture (aasana), spiritual breathing (pranaayama), withdrawal from sensory stimuli (pratyaahara), meditation (dhyaana), contemplation (dharana), and profound meditation or trance (samaadhi) (Dwivedi 1979: p.49).

The study of the eightfold path makes it clear that Patanjali's yoga is passive, and in this it is different from the karma yoga of the Gita. The passivity of Patanjali's method implies the suspension of all movement, physical as well as mental, on the part of the yogi in communion with the supreme, thus it is comparable to some aspects of the virtuous meditation of Jainism.

Buddhism also has meditation as a central practice of its spirituality. Buddhists meditate to comprehend the true nature of reality and to develop in harmony with it. Gautama, the Buddha, learned the art of meditation from Jain teachers before his enlightenment. The chanting of a mantra or sacred verses encourages mental calmness; the rhythmic ebb and flow of breath is used as a focal point to which the attention is brought back whenever it wanders; this type of meditation is called 'peaceful abiding' (samataa). Those engaged in meditation can progress to the technique called 'introspection' (vipassanaa), by which they hope to gain insight into reality. This is achieved by looking inward beneath the surface of consciousness. They are aware of deep underlying emotions and thoughts, but refrain from interacting with them to dampen their activity. Meditation means being totally aware of the present moment and once this is well established, meditation can be practised when standing, sitting, walking or lying down. The Buddha is portrayed as being mindful in all these states. Zen Buddhism particularly emphasises that meditation can be performed while carrying out the most basic activities of life. In the Theravada tradition of South East Asia, meditation has traditionally been viewed as largely the work of ascetics, particularly those who choose to live isolated and solitary lives in the forest, but nowadays, laypersons meditate either with ascetics or in lay meditation centres. Buddhist meditation compares favourably with some aspects of Jain virtuous meditation.

Meditation practices and their beneficial effects have been well known in India for thousands of years, but Indian meditation practices have only recently become widely appreciated in the West. Meditation helps to promote both physical and spiritual health, and in India many institutions employ meditation practices to assist the cure of illnesses and to establish the scientific basis of meditation. Jain meditation has been interwoven into the daily activities of the Jain community. It is believed that this has contributed to the lessening of certain illnesses in the Jain population.

It is outside the scope of this work to describe fully the techniques of meditation. The reader is referred to the many works published on the subject.

Dr. Natubhai Shah

Dr. Natubhai Shah