It is not unusual to hear people criticising Jainism as an atheistic religion. Such of the criticising as are followers of the Hindu theistic philosophy base their view on three grounds: The Jainas do not believe in a personal god, the authority of the Vedas and in the existence of the life beyond. It must be conceded that the Jainas do not accept the authority of the Vedas because the teachings of the Tīrthankaras are opposed to the Vedic type of rituals, the sacrifices and the existence of numerous gods extolled therein. The Jainas accept rebirth and the existence of life after death.

The word Nāstika has been differently interpreted. Panini's sutra (asti nāsti disṭaṃ matīh) has been interpreted to mean that he who does not accept paraloka or life after death is a nāstika. According to the Nyāyakośa, a nāstika is a person who does not accept the existence of Īśvara. Manu has said that he who derides the authority of the Vedas is a Nāstika (Nāstika Vedanindakaḥ). Acceptance of the authority of the Vedas does not enter into the concept of atheism. "Atheism, both by etymology and usage, is essentially a negative conception and exists only as an expression of dissent from the positive theistic beliefs. Theism is the belief that all entities in the cosmos, which are known to us through our senses or inferred by our imagination and reason, are dependent for their origination and for their continuance in existence upon the creative and causal action of an infinite and eternal Self- consciousness and Will; and in its higher stages, it implies that the Self-existent Being progressively reveals his essence and character in the ideas and ideals of His rational creatures, and thus stands in personal relationship with them. In the early stages, theism conceives of God simply as the Cause and Ground for all finite and dependent existences; but as it develops, it realises the idea of God as immanent and self- manifesting as well as creative and transcendent"[1]

It seems to me that the term atheism itself appears to have undergone a change in its meaning just as the idea of God has varied with the founders of different religions.

The most common concept of a personal God is that he is the supreme being who creates the world and rules over it; he presides over the destinies of all living creatures and awards rewards or punishments according to the merits or sins committed by each individual. In the Bhagavad-gītā, Sri Kṛṣṇa says: If any devotee desires to worship the idol of a God with devotion, I grant him unshakeable faith in that God only. He worships that God endowed with that faith and he gains his desires, for it is I who bestow the same on him."

As regards His attribute of power of creation Swami Vivekananda said: ;'What makes this creation? God. What do I mean by the use of the English word God? Certainly not the word as ordinarily used in English-a good deal of difference. There is no other suitable word in English. I would rather confine myself to the Sanskrit word Brahman. He is the general cause of these manifestations. What is Brahman? He is eternal, eternally pure, eternally awake, the almighty, the ail-knowing, the all-merciful, the omnipresent, the formless, the part less. He creates this universe."[2]

During the primitive days of civilization, man regarded the most powerful elements of nature, like fire, wind, rain etc. as gods. He must have wondered nursing over impregnable nature and conceived of many forms as worthy of worship by propitiating through various kinds of offerings including sacrifice of animals etc. Referring to ancient Judaism which regards Jehovah as the Maker of the Universe and of two human beings Adam and Eve, Robert Bridges, the former Poet Laureate of England wrote:

"I wondered finding only my own thought of myself, and regarding there that man was made in God's image and knew not yet that God was made in the image of man; nor the profounder truth that both these truths are one, no quibbling scoff-for surely as mind in man groweth so with his manhood groweth his idea of God, wider ever and worthier, until it may contain and reconcile in reason all wisdom, passion and love, and bring at last (may God so grant) Christ's peace on Earth."[3]

If we consider the concepts of numerous faiths in the world, we would know undoubtedly that the forms of God as conceived in Purāṇas and mythologies are legion and that these Gods are supposed to protect their devotees from evils or grant them their desires if they were pleased with their worship and offerings. Amongst the Hindus, the Trinity of Brahma, Viṣṇu and Maheśa has been popular in conception. The followers of Viṣṇu and Maheśa or Siva regard their own God as worthy of worship and the other as a subordinate God. Amongst them, we have stories of Viṣṇu with his ten Avatāras always ready to protect the weak and to save his devotees from the hands of the wicked. Sarasvatī, Lakṣmi and Pārbati are respectively the wives of these gods. Numerous legends have been told of Siva also. There are many lesser gods, like indra, Yama, Varuṇa Kubera etc. It is unnecessary to refer to their functions and powers in the scheme of preservation or protection of the universe.

Jainism does not recognise that the universe was created by any God or gods. The universe is external and uncreated. It is subject to integration and dissolution in its forms and aspects. It is constituted of six substances viz. Soul, matter, time, space, principle of motion, the principle of stationaries. It is a compound of these substances Soul is characterised by consciousness while the matter is not. Thai is consistent with scientific theories. From the stand point of reality, the soul is free and formless. Matter has form. The number of souls in the universe is infinite.

The Jaina idea of God is that of a pure soul possessed of infinite faith, knowledge, bliss and power. These qualities are inherent in the soul itself but they are either destroyed or veiled by the four kinds of Karmas: Darśanāvaraṇīya, Jñānāvarṇīya, Mohanīya, and Antaraya. Perfect faith is attained by the destruction of the first kind of Karma while perfect knowledge is attained by the total destruction of the second kind of Karma. Infinite happiness and power are attained by the destruction of the other two Karmas. The four qualities are not a gift from anybody but they are inherent in the very nature of the soul. The Jaina philosophers call such an Arhat who is popularly called God, Sarvajña, Vītarāga, Paramātmā, Jina etc. He is essentially a conqueror of all passions and attachments. He is also called Āpta or the Tīrthankara as he has shown the path of liberation from the miseries and the travails of the Samsara. He is characterised by absolute freedom from eighteen kinds of weaknesses viz. hunger, thirst, fear, aversion, attachment, illusion, anxiety, pride, displeasure, astonishment, birth, sleep and sorrow.4 From the realistic point of view, the Arhat is without a body while from the popular point of view, he possesses a body known a Audārika which has the brilliance of thousand suns.

Such a God is full of effulgence due to infinite knowledge and bliss. He has no desires or duties. He does not interfere in the affairs of men or inflict upon himself the management of worlds, and he would not waste his time in creative activity in any form. A God should have no unfulfilled purpose, or unsatisfied cravings or ambitions; and, for this reason, he should not manage or create a world.[4]

The concept of Arhat or God is quite consistent with the view that he cannot be a Creator, Ruler or Regulator of a world which is uncreated and eternal. Creation implies desire on the part of the God who wants to create; desire implies imperfection. A. B. Lathe has quoted the reasoning of an Acarya on this point: "If God created the universe, where was he before creating it? If he was not in space, where did he localise the universe? How could a formless or immaterial substance like God create the world of matter? If the material is to be taken as existing, why not take the world itself £S unbegun? If the creator was uncreated, why not suppose the world to be itself-existing?....Is God self-sufficient? If he is, he need not have created the world. If he is not, like an ordinary potter, he would be incapable of the task, since, by hypothesis, only a perfect being could produce it. If God created the world as a mere play of his will, it would be making God childish. If God is benevolent and has created the world out of his grace, he would not have brought into existence misery as well as felicity."[5]

In brief, the Jainas do not accept the view of the Naiyāyika that the world is created by an intelligent agent who is God; nor do they accept that he is omnipresent because if he exists everywhere, he will absorb everything within himself, without leaving anything to exist outside him. They do not regard God as necessary to explain the universe. Each individual soul is divine in its nature and can attain perfection. The concept of God in Jaina philosophy is the divinity in man. Man can realise the same by cultivation of steady faith, right perception, perfect knowledge and a spotless character. Man has absolute independence and nothing can intervene between his actions and their fruits. Such Philosophy does not appeal to the weak minds. Men and women in difficulties look up to some divine power which could aid them in their difficulties and relieve them of their sufferings. They pray for favours and gifts, forgetting that they are the makers of their own destinies and that their joys and sorrows are of their own making. Perhaps to bring solace to such minds, the cult of Yakṣas and Yakṣiṇīs seems to have taken birth at some later stage. According to Hiralal Jain, the Jainas accorded a place in their temples to the Yakṣas, Nāgas and other gods and goddesses by picturing them as guardians of the Tirthankaras out of respect for the sentiments of the non-Aryans who used to erect temples for them. Once the Yaksa cult was prevalent in India and so also of the Yakiṣiṇ, in different forms. They were Kuladevatās. When groups of people adopted the Jaina way of life, they brought these Kuladevatās with them and the Jaina Ācāryas gave them a secondary place in the Jaina pantheon and used them for ritualistic purposes.

The Jaina Purāṇas do refer to the Yakṣas and Yakṣinīs. Dharaṇendra and Padmāvatī have been associated with Tīrthankara Pārśvanātha whom they are said to have protected from the cruel attacks of his enemy to disturb him during his meditations. They are worshipped by holding out promise of offers of things if their desires are fulfilled. The forms of worship with tāntric and māntric rituals are foreign to Jaina philosophy. However, the worship of these gods and goddesses must have been thought of to wean away ordinary men and women from the influences of Hinduism which holds out the hope of fulfilment of one's own desires by a number of gods and goddesses. T. G. Kalghatigi says "The cult of Jvālāmālini with its tantric accompaniments may be mentioned as another example of this form of worship. Tue promulgator of this cult was perhaps, Helācārya of Ponnur. According to the prevailing belief at that time, mastery over spells or Mantravidyā was considered as a qualification for superiority. The Jain Ācāryas claimed to be master Mantravādins. Jainism had to compete with other Hindu creeds. Yaks! form of worship must have been introduced in order to attract the common men towards Jainism, by appealing to the popular forms of worship."[6]

According to Jaina metaphysics, one of the four states of existence is the Deva-gati in which a soul may assume on account of its good Karmas the Deva-gati living in heaven like the Bhavanavāsi, Vyantaravāsi, Jyotiṣka and Kalpavāsi. These gods are subject to birth and rebirth and are unable to grant any favours to other beings. They are a stage higher than men but they must be reborn as men if they have to attain complete liberation from the cycle of births and deaths. Their abode is fixed as the celestial region where they live enjoying the fruits of their puṇya or meritorious deeds till the puṇya is exhausted. They have ranks amongst them either based on status or duration of life.

The Jainas recognise divinity in man, and godhood means the attainment of purity and perfection inherent in every soul Tirthankaras are among those who have attained omniscience and perfection.

The Concept of Worship.Why do the Jainas worship the Tirthankaras? They worship them because they are liberated souls who have attained perfection and omniscience. They were mortals; they looked to no higher beings but looked within themselves. They are the prophets who held aloft the light of Jaina religion and culture. They preached the eternal truths of life, followed them and helped millions of other men to cross the hurdles of Samsara. They realised the divinity of their soul. In worshipping Tirthankaras, a Jaina worships the ideals followed and preached during their journey to self-realization. He seeks no favours because a Tirthankara can grant none. There is nothing like divine grace unless one cultivates divinity by elevating one's own soul.

Umāsvāmi has expressed the object of worship in precise terms in the opening verse of his renowned scripture known as the Tattvārtha-Sutra which is an aphoristic exposition of the principles of reality.

"Mokṣamārgasya netāraṃ bhettāram karmabhūbṛtām

Jnātāraṃ viśvatattvānāṃ vande tadguṇalabdhaye."

I bow to the Lord who is the leader of the path of liberation, the destroyer of the mountains of karmas and the knower of the whole of reality, so that I may realise those qualities.''[7]

The object of this worship therefore is not to seek favours but to cultivate a frame of mind which will develop in oneself all that is best in the master. The devotee is in the position of a disciple who approaches his Master in his lonely hut seeking for new light and guidance to attain liberation. Pūjyapāda has given an example in his exposition of the above verse: "Some wise person who is desirous of obtaining what is good for him and who is capable of attaining liberation in a short time, approaches a lonely and delightful hermitage capable of affording peace of mind to the potential souls. There he sees the preceptor, seated in the midst of the congregation of monks as the embodiment of the path to liberation as it were indicating the path by his very form even without uttering words. He comes before the great passionless saint, skilled in reasoning and in the scriptures, who is worthy of veneration by noble persons and whose chief task is to preach what is good to all living beings. The disciple asks him with reverence' Master, what is good for the soul? The saint says: 'Liberation'. He again asks the saint, 'What is the nature of liberation, and what is the way to attain it V The saint answers 'Liberation is the attainment of an altogether different state of soul, on the removal of all the impurities of Karmic matter and the body, characterised by the inherent qualities of the soul such as knowledge and bliss, free from pain and suffering.'[8]

Seeking guidance by reminding ourselves of what has been preached by the Tirthankaras and what is said in the scriptures is the object of worship. This is possible only by purification of the mind and thoughts so that the moments of worships are really the moments of meditation on the real nature of the Self.

All religions prescribe a form of daily prayer. The contents of the prayer are indicative of the psychological approach of the devotee. The full prayer is as follows:

"Oṃ ṇamo Arihantāṇaṃ, ṇamo Siddhāṇaṃ,

ṇamo Āyariyāṇaṃ, ṇamo Uvajjhāyāṇaṃ,

ṇamo ḷoe savvasāhūṇaṃ."

''Obeisance to the Arhat,

obeisance to the Siddhas,

obeisance to the Ācāryas,

obeisance to the Upādhyāyas and

obeisance to all the Sādhus in the universe."

This mantra is called the Pānoaṇamckāra mantra as it is a prayer of the Pāncaparameṣṭhis, that is, the five Supreme Beings who are to be revered by our respectful salutation. There is nothing sectarian about it. It concentrates itself on the merits and qualities rather than on any particular god or teacher.

The qualities and ideals which each of the five Supreme Beings represent are explained by Nemichandra in verses 50 to 54 of his book 'Dravya-Samgraha' (A Compendium of Dravyas).[9]

While dealing with the concept of God above, I have already dealt with the qualities of an Arhat. He is a pure soul in an auspicious body, (śubha-dehastha), possessed of infinite faith, happiness, knowledge and power, which has destroyed the four destructive karmas. From a realistic point of view, an Arhat is without a body; but from the popular point of view, we speak of him as possessed of a lustrous body.

When we meditate upon the Siddha, we meditate upon the soul which is without a body produced by eight kinds of karmas; he is the seer and knower of Loka and Aloka and he stays at the summit of the Universe. The Siddha is without a body and cannot therefore be perceived by the senses. His shadowy shape resembles a human figure. The summit of Lokākāśa where he stays is called Siddha-śilā. According to Jainism, a Siddha has knowledge of everything in the Lokākāśa and Lokākāśa which existed in the past, exists in the present and will exist in the future. These Siddhas have to be distinguished from the ordinary Sādhus who are supposed to possess some miraculous powers.

The Ācārya who is to be meditated upon is one who practises five kinds of conduct. The five Acaras are Darsanacara Jnanacara, Caritracara, Tapacara and Viryacara. Darśanācāra consists in cultivating faith in the soul which consists of Supreme Consciousness and is the only thing to -be meditated upon as it is separate from the body. Jñānācāra consists in developing knowledge that the soul is pure and perfect, and that it has nothing to do with attachment, delusion, or aversion, Cāritrācāra consists in moulding one's own conduct by freeing it from all kinds of attachments and other disturbing factors so that the mind can have the necessary calm and tranquillity for peaceful contemplation on the nature of soul. Tapācāra is practising various kinds of penances and austerities so as to enable the soul to attain its true nature. Viryācāra consist in the development of one's own power or inherent strength of all the mental faculties so that the soul feels no hindrance in self- realization. An Acarya who preaches and practises these qualities is worthy of respect and veneration.

Upādhyāya or a teacher is one who is possessed of the three Jewels and is ever engaged in preaching the tenets of religion. He is accorded a high place of honour because it is he who inspires the people by 'his preachings to religious pursuits and practices.

A Sādhu is one who walks into the path of liberation with perfect faith and knowledge and with all purity of thought and conduct. He practises penances and engages in activities which are conducive to attainment of liberation.

These are five supreme beings who are to be praised and revered every day. They are possessed of qualities which, when contemplated upon, are sure to conduce to peace of mind to moulding of conduct and lead to clear perception and real knowledge of the true nature of the soul. The first stage of meditation is attainment of steadiness in conduct while the second stage is reached when concentration in the contemplation of the soul is reached The mind is freed from attachment to or desire for acquisition of worldly possessions. Mental weaknesses like delusion, aversion, anger, hatred, pride, greed etc. are overcome so as to acquire complete equanimity of mind. This is the firbt stage of preparation for meditation. Then one should turn all his faculties inward with complete restraint of mind, thought and action in relation to external objects, and meditate on the nature of the soul. This is what is called Dhyana. It is essential that the person who wishes to practise meditation should prepare the preliminary ground by acquisition of knowledge of scriptures, observance of the various vows and practice of penance.

This is the real conception of Jaina prayer and worship. It is impossible to know fully well the qualities of the Five Supreme Beings or the Panca-Parameṣṭhis without regular study of the scriptures. Knowledge of the scriptures strengthens our faith in religion and creates an awareness of the inherent potentialities of the soul.

The special features of Jaina worship and prayer have been briefly noted by J. L. Jaini: "Four points must be noticed:

- the catholicity of the Jaina attitude. The worship and reverence are given to all human souls worthy of it, in whatever clime or country they may be. The worship is impersonal.

- It is the aggregate of the qualities that is worshipped rather than any particular individual.

- The Arhat, the living embodiment of the highest goal of Jainism, is named before the free soul who has left the world and cannot be approached by humanity which requires to see the truth before it can seek it

- The Jaina incantation aum or Om is composed of five sounds: a, a, ā, u and m which stand respectively for arthat; aśarira ("disembodied" i. e., the Siddha); ācārya; Upādhyāya and muni-the silent or the sadhu. The prayer and worship are media through which we not only exhibit our ideal but also develop devotion which raises us to a stale of ecstasy making us supremely happy in the realization of ourselves.

One thing that must be added in conclusion is that inspite of the idealistic concept of God, Jaina saints and poets have taught their followers to be tolerant of other religions. Their doctrine of Anekāntavāda is perhaps responsible for their cosmopolitan outlook as it enables him to appreciate the other's point of view. Here is a verse from the pen of a Jaina saint which says, in effect, that it is immaterial by what name you call your god as all gods possess the common qualities of purity, compassion and divinity.

"Viṣṇurvā Tripurāntako Bhavatu vā Brahmā Surendrothavā, Bhānurva Śasilānchanotha Bhagavān Buddhotha Siddhothavā Rāgadveṣāviṣārti doṣarahitaḥ satvānukampodyato, yah sarvaiḥ saha saṃskṛto guṇagaṇaistasmai namaḥ sarvadā." ''Let me always salute him who is free from blemishes of anger, hatred etc., which haunt the mind like poison, who is full of compassion and who has perfected himself by all virtues, whether he is called by the name of Viṣṇu, Siva, Brahma, Devendra, Sun, Moon, Bhagavān or Buddha."

Let me quote the following passage from J. L. Jaini who summarises the concept of God in Jainism in simple but forceful words; "Jainism, more than any other creed, gives absolute religious independence and freedom to man. Nothing can intervene between the actions which we do and the fruits thereof. Once done, they become our masters and must fructify. As my independence is great, so my responsibility is co-extensive with it. I can live as I like; but my voice is irrevocable, and I cannot escape the consequences of it. This principle distinguishes Jainism from other religions, e. g. Christianity, Muhammadanism, Hinduism. No God, or His prophet or deputy, or beloved, can interfere with human life. The soul, and it alone is responsible for all that it does".[10]

In conclusion, Jainism does not accept the existence of a personal God who is at once the creator and protector. The real God is the soul which has attained perfection. Infinite perception, knowledge, power and Bliss which are the attributes of perfection are inherent in every soul. In the material world those attributes are hidden by the veils of the Karmas. The Tirthankaras who are the ideals of perfection have shown the way of liberation. He who follows the requisites of Right knowledge and Right conduct can attain divinity by the fullest realization of the; powers which lie dormant in him.

James Hastings (Editor): Encyclopeadia of Religion and Ethics, Vol. II. p. 173. Edinburgh, T & T Clark, 38 George Street, New York

Svami Vivekananda: Lectures from Colombo to Aimer a pp. 21. Advaita Ashram, 5 Delhi Entally Road, Calcutta-14

Jain, C. R.: Jainism and World Problems, p. 125. The Jaina Publishing House, Bijnor (U. P.) India 1934

Jain, S. A.: Reality (Tattvartha Sutra), Sutra L Vira Sasana Sangha, 29 Indra Visvas Road, Calcutta 37

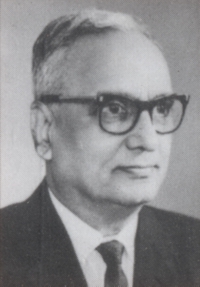

Justice T.K. Tukol

Justice T.K. Tukol