I was 15 when Bhagwan came to Erode, the city where I lived. He showed us the Jain kriyas, the ways to maintain patience, to sit in meditation. I had never seen that before.

I was 15 when Bhagwan came to Erode, the city where I lived. He showed us the Jain kriyas, the ways to maintain patience, to sit in meditation. I had never seen that before.

I was in 10th grade, and had decided that I was going to study medicine. But Bhagwan’s teachings began to make an impression on me. When he would preach to us, his talks made a path full of thorns feel like one full of roses. Another holy man from the temple, Rajesh Muni Ji, said, if you become a doctor, you help only a limited number of people, those who live around you. But, he said, if you choose the path of abstinence from material things, you can help all the living beings in this universe.

There was a lot of turmoil in my mind when I thought about what they said. There was a churning. I started thinking deeply about the tenets of Jainism. There are so many things, living and dead, around us. The mud, the soil, the stone, the water. Fire. Green plants that we trample. Things that we kill when we construct a building or step in the water. Unconsciously, we are causing pain. The whole idea of Jain sainthood is to live without causing any pain.

Until then, all conversation in my family centered on how difficult it would be to become a doctor. My mother helped me get into the best schools. But three days after I started 11th grade, I said that I didn’t want to be a doctor anymore. She said, “Talk to your father, don’t tell me this.” Everyone was telling my parents, “Get the girl back here, she needs to be home with her family.” My grandparents were ill at what I was going to do.

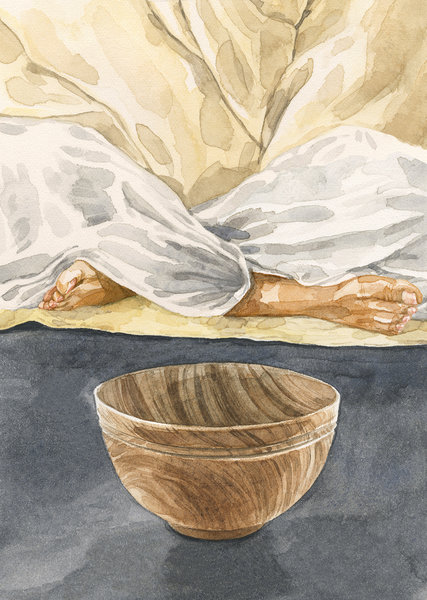

What will I give up when I take diksha? I will give up all vehicles, mobile phones, cosmetics, colorful clothes, footwear, money, ornaments. Renouncers can have only white clothes, just a few of them. You are allowed to own only books about Jain religion, a bowl in which we can eat food and the broom we use to clear the path that we walk on.

We get up at 4, meditate at 4:30. From 4:30 to 5, we hear scriptures. There is no electricity, so whatever we learn is what we say out loud. From 5 to 6, we do yoga. From 6 to 6:30, we do meditation. There is a ritual in which we look at every bit of the objects we use - the flap, the sheet we lie on, the blanket, this broom - to see if there is any living thing on it, for instance, an ant. If we see something, then we put it aside so as not to kill it.

Then we eat. In Jain sainthood, food is not eaten for the taste, but to maintain the body so that it can continue the practice of abstinence. Before going to bed, we do a ritual called alochana, self-criticism. You go through the day’s activities and think about the times you could have hurt something or killed a bug. In pratikraman, or introspection, we repent for any of these sins we have committed in daily life.

About six months ago, my family approved my request to take diksha. On that day, I will be decked out at 4 a.m. in a multicolored sari. You are seen off by everyone in your family. It’s called vidai, or farewell. There is a hall called a mundan sthal, a shearing place, where my hair will be shaved off.

Two or three strands of hair are left after the shearing. A senior saint will just pluck that hair off my head. You have to bear the pain. It is penance. We believe that the soul keeps getting covered under layers of our actions. If you kill an ant, small actions like that, you keep covering your soul, layer upon layer. To remove those layers, we do penance.

After that, I begin a life of sainthood. Earlier, food was cooked for us, but that will be over. We will go from house to house and ask for food. If the door is open, we come in - we never knock. If there is something extra, we will take that, or if there is food not fit for consumption. If we lodge in a place where there is fire or water or electricity, we cannot use these things.

This life I will be leading is unimaginable. There is immense happiness. There is excitement. That is also not acceptable, to keep excitement inside yourself. We are supposed to be consistent, not to have highs and lows. It will take some practice to gain that level of moderation.

My school friends have been left behind. There’s no point in thinking about where they will be in 10 years. A mobile phone? My new life will be old-fashioned in the sense that it is just about ourselves. Modern and old-fashioned, this thing and that thing, they will all end like this piece of paper. If we burn it, it will become ash. Our soul is never-ending. It will be there for all of time - not just the whole life, the whole everything.

As told to Ellen Barry

Illustration by Melinda Josie