Vardhmansuri and Jinesvarsuri had many illustrious successors. Among them, however, the ones who stand out most in the ritual life of Jains associated with the Khartar Gacch are the four Dadagurus. And of the Dadagurus, none is of greater importance than the first, Jindattsuri.

Jindattsuri was born in 1075 C.E. at a place called Dholka.[1] His clan was Humbad and his given name was Somcandra. When he was a small boy he once accompanied his mother to discourses being given by some Khartar Gacch nuns. They noticed auspicious marks on the boy, became convinced that he was destined for greatness, and sent news of their discovery to a senior monk named Dharmdevji Upadhyay. This monk then came to the village and asked the boy's mother if she would be willing to "give the boy to the sangh" (the conventional expression for allowing a child to be initiated). Parental permission was given, and the boy's initiation occurred in 1084 when he was only nine years old.

Somcandra demonstrated cleverness and great independence of mind from the start. His education was put in the hands of an ascetic named Sarvadevgani. Dharmdevji told Sarvadevgani to educate the boy in every particular of the mendicant's life, and even to take the boy with him to the latrine.[2] Somcandra, however, was very young and ignorant of the rules of ascetic discipline. Knowing no better, he uprooted some plants in the field. In his exasperation, Sarvadev took away the boy's mouth-cloth and broom and told him to go home. The boy responded that if Sarvadev wanted him to go, he'd go, but first he'd like the hair that had been taken from his head (in his initiation ceremony) returned. Sarvadev was highly impressed by this spunky response, as was Dharmdevji when it was reported to him.

After his studies were completed, Somcandra began his wanderings from village to village. He impressed everyone with his learning, meditation, and piety. As time passed his reputation grew to such an extent that, when Jinvallabhsuri - the leader of the Khartar Gacch at that time - passed away, Somcandra was his logical successor. He attained the status of acarya at Cittaur in the year 1112, at which point he acquired the name Jindattsuri and assumed the leadership of the Gacch.

Wishing to know where he should go in his wanderings, the newly elevated Jindattsuri engaged in a program of meditation and fasting. According to the hagiographies, a deceased ascetic named Harisinghacarya came to earth from heaven in response. He told Jindattsuri that he should go to Marwar and places like it. Jindattsuri followed this advice, first going to Marwar and then to Nagpur, and later through countless villages and towns. He taught, he protected the Jain faith, and he converted many non-Jains to Jainism. His rainy season sojourns were sources of inspiration in the communities in which they occurred. He performed numerous consecrations of images and initiations of ascetics. He was also a great reformer. Under his influence, large numbers of Caityavasi acaryas abandoned their former ways and took initiation with him. He had many admirers among great kings and princes. Arnoraj, the then-ruler of Ajmer, was one of the kings of the period who numbered among his devotees.

He seems to have been tough-minded and earthy, qualities of character that probably served him well in a pattern of life that was surely merciless in its physical and psychological demands. Once in Nagpur a certain rich man presumptuously tried to advise Jindattsuri on how to gain more followers. The monk responded with a verse that reveals a man with a short fuse who did not suffer fools gladly. This verse is translated by Phyllis Granoff (1993: 55) as follows:

Do not think that just because he has many hangers-on a man is honored in this world For see how the sow, surrounded by all her young, still eats shit.

He was, above all, a great worker of miracles, as were all the Dadagurus. It is extremely important to emphasize that the hagiographies insist that these miracles always had a higher purpose than merely solving someone's worldly problems. From the standpoint of Jainism's highest ideals, ascetics are not supposed to be magicians. As we have already seen in the case of Chagansagar, the hagiographers must therefore legitimize this power by establishing a Jain context for it. One legitimizing strategy is to accentuate the point that the miraculous power is associated with its possessor's asceticism. Another strategy is to stress that the purpose of the miracles was always to glorify Jain teachings or to help Jainism flourish. The miracle-working ascetic protects Jain laity, defeats Jainism's enemies, and often aids non-Jains, who may become Jains as a result (the subject of the next chapter).

In Jindattsuri's case, however, the hagiographies establish yet another legitimizing frame of reference for magical power. It seems that Vajrasvami, a legendary ascetic from centuries earlier, had written a book of ancient knowledge (presumably magical).[3] Because he lacked any disciple who could make proper use of this knowledge, he secreted the book in a pillar in the fort at Cittaur. Others had tried and failed to obtain this book, but by means of his own yogic power (yogbal) Jindattsuri was able to acquire it and derive powers from it.[4] This tale makes the point that Jindattsuri's power derives both from sources internal to himself (his own yogic ability) and from an interrupted tradition of magically potent ascetics. Legitimacy is conferred on this connection, in turn, because it is embedded in the longer line of disciplic succession connecting Jindattsuri to Lord Mahavir.

Many of Jindattsuri's miracles - which cannot all be described here - involved subduing non-Jain powers.[5] An example is his victory over the five adhisthayak pirs of the five rivers of Punjab who once tried to disturb him in meditation[6] It is said that because of his powers of concentration they found it impossible to budge him, and as a result the five pirs conceded defeat by standing before him with hands joined, after which they became his servants. The fact that these non-Jain powers are depicted as pirs, which refers to Muslim saints, may reflect the fact that Muslim influence was particularly strong in this region. It is also said that he subdued fifty-two bhairav virs (forms of the deity Bhairav), who also became his servants. Bhairav (or Bhairava) is a form of Siva, and this episode may mirror Jain conflict with the Saivas, which was ongoing at the time.

Another example was his defeat of sixty-four yoginis: malicious, non-Jain, female supernaturals.[7] The incident occurred in Ujjain, where Jindattsuri had begun a public discourse. He told his listeners that the sixty-four yoginis were coming in order to create a disturbance,[8] and that they should spread sixty-four mats and seat the yoginis on them. The sixty-four arrived disguised as laywomen, and were duly seated on the mats. Jindattsuri cast a spell on them by means of his special power, and then resumed his discourse. When the other listeners rose at the end, the yoginis were unable to leave their seats. They then were ashamed and said to Jindattsuri that although they had come to deceive him they had in fact been deceived themselves. They begged forgiveness and promised that they would assist him in propagating Jainism. This episode possibly reflects Jain opposition to cults of tantric goddesses and may also echo the theme of the taming of the lineage goddesses, which will be explored in the next chapter.

He also used his miraculous powers against Jainism's human opponents. Once at a place called Badnagar some Brahmans tried to disgrace Jindattsuri and the Jain community by having a dead cow placed in front of a Jain temple. In the morning the temple's pujari discovered the outrage. He told the tale to the chief businessman of the city, who in turn told Jindattsuri. By means of his knowledge of how to enter other bodies Jindattsuri caused the cow to rise, walk, and expire again in front of a Siva temple. Here the opponents are both Brahmans and Saivas. In another version of the same story, the Brahmans put the corpse of a Brahman in front of a Jain temple, and Jindattsuri caused the Brahman corpse to rise and expire again in front of a "Brahman". temple (Granoff 1993: 65).

Jindattsuri even defied the fury of nature on behalf of Jainism. Once, in Ajmer, a fearsome stroke of lightning in the evening threatened a group of laymen performing the rite of pratikraman. Jindattsuri caught the lightning under his alms bowl and the rite was able to proceed.

Jindattsuri is said to have had the title of yugpradhan (spiritual leader of the age) bestowed upon him in a miraculous fashion.[9] It seems that in order to find out who was the yugpradhan, a layman named Nagdev (Ambad in some accounts) went up to the summit of Girnar[10] and fasted for three days. Pleased by his austerities, the goddess Ambika Devi appeared and wrote the yugpradhan's name on his hand, saying, "He who can read these letters, know him to be the yugpradhan. "Nagdev traveled far and wide and showed his hand to many learned acaryas, but nobody could read the letters. In the end he went to Patan, where he showed his hand to Jindattsuri. The monk sprinkled vasksep powder on the letters and they became clear. It was a couplet that read as follows: "He at whose lotus feet all of the gods fall in complete humility, and who is an oasis-like kalptaru (wish-fulfilling tree), may that yugpradhan who is Sri Jindattsuri be ever-victorious."

Jindattsuri's life ended at Ajmer in 1154 C.E. When he realized that the end was near, he ceased taking nourishment and died on the eleventh day of the bright fortnight of the month of Asarh. At the time of his cremation, his clothing and mouth-cloth failed to ignite, and they are said to be preserved to this day in Jaisalmer. His successor, Jincandrasuri" Manidhari," established a memorial on the spot on which his body was burned, and this was later made into a proper temple.

After death Jindattsuri became a god. According to one account (Vidyut Prabha Sri 1980: 11), Simandhar Svami (a Tirthankar currently active and teaching in the continent of Mahavideh) was once asked by his guardian goddess (sasandevi) where Jindattsuri had been reborn. The omniscient Simandhar replied that at the present time he was in devlok (heaven), and that after a sojourn there he would take birth in Mahavideh and there achieve liberation. Another author (Suryamall 1941: 32 [appendix]) also states that Jindattsuri became a god in the Saudharma Devlok and will ultimately return to the region of Mahavideh, whence he will attain liberation.

The following accounts of the lives of the Dadagurus are based on A. Nahta (1988), A. and B. Nahta (1939, 1971), Vidyut Prabha Sri (1980), and Vinaysagar (1959, 1989). For an English version of Jindattsuri's life translated from the Khartargacchbrhadguruali, see Granoff 1993.

The miracle of the book at Cittaur is also attributed to Siddhasena, another distinguished ascetic. Here, too, the monk obtains magic powers from the book (or books). See Granoff 1990: 265-66

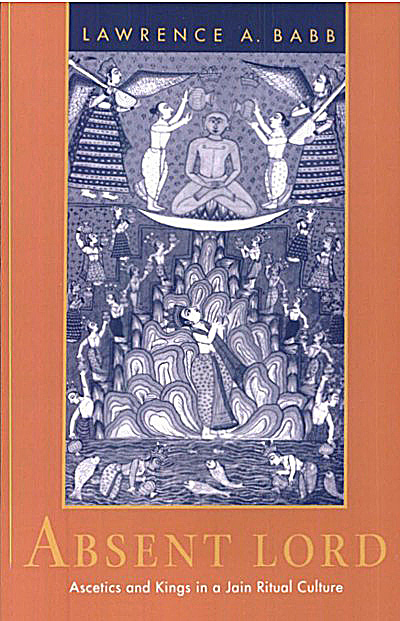

The miracles described here and also for the other Dadagurus are described in virtually all accounts of their lives. In many temples and dadabaris they are portrayed in vivid illustrations on the walls. In addition, they are described in the text of the Dadagurus' most important rite of worship (to be discussed later in the chapter). Most devotees of the Dadagurus know them well.

On the five pirs, see William Crooke 1978: 202-3, 206. He suggests that they are possibly Muslimized versions of the Mahabharata's five Pandavas.

A similar story is told of the great fourteenth-century Khartar Gacch leader, Jinprabhasuri (see Granoff 1993: 25). Sixty-four yoginis attended his discourse disguised as laywomen. He cast a spell on them and they were unable to rise from their seats. They then begged for forgiveness.

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb