What is this rite about? Its performance is, in part, seen as a source of auspiciousness and benefit to those who participate in it. This is a theme to which we shall return in the next chapter. In its narrative dimension, however, it is concerned with the nature of worship-worthiness. The most worship-worthy of all beings is the Tirthankar. This is because he leads the ideal life, and Parsvanath's five-kalyanakpuja is, at its textual core, a celebration of such a life.

The rite tells us first of all that the ideal life has a transmigratory context. This is a point often missed in English-language accounts of Jainism in which attention is usually focused entirely on the Tirthankars' final lifetimes. To Jains, however, one of the crucial things about a Tirthankar is that his final lifetime is indeed his final lifetime, the last of a beginningless series of rebirths. It must be stressed that, from the Jain point of view, a lifetime considered outside the context of the individual's transmigratory career is meaningless. We shall consider this point in greater detail later in this chapter.

In conformity with hagiographic convention, the text recounts Parsvanath's previous births beginning with the lifetime in which he obtained "right belief" (samyaktva). This is a crucial idea in Jainism. Jains say that once the seeds of righteousness have been planted, progress is always possible, no matter what the ups and downs in the meantime. An Ahmedabad friend once told me that if you possess right belief for as little time as a grain of rice can be balanced on the tip of the horn of a cow, you will obtain liberation sooner or later.[1] Therefore, even if one has little immediate interest in the ultimate goal of liberation or little sense of its personal gainability - which is in fact true of many ordinary Jains - one can still believe that one is on the right road if one has been touched by Jain teachings and if one has the necessary "capability" (bhavyatva). How does one know who is on this path and who has this capacity? Such persons are, surely, among those who celebrate the Lord's kalyanaks and who do so in the proper spirit of devotion and detachment from worldly desires.

Parsvanath's transmigratory career then takes a decisive turn. His destiny is fixed when he acquires the karma of a future Tirthankar two births before his final one. He has reaped the rewards of his virtues, but these he sees in the perspective of a fully realized detachment. The rite then draws our attention to his penultimate existence as a god. Other gods mourn their impending earthly rebirths. Not so the Tirthankar-to-be, for he regards the fall into a human body as an opportunity. This is a crucial matter, for it marks the separation of two possible paths. Divine and earthly happiness is the inevitable reward of virtuous action. This the Tirthankar-to-be achieves in abundance, but he is completely indifferent to it. His is another goal. Felicity is a shackle, albeit (as Jains frequently say) one of gold.

The text thus illustrates a choice, and in theory Parsvanath might have chosen differently. His virtues bear the fruit of material rewards. The highest of these is rebirth as a deity. But this he rejects. Parsvanath-to-be does not regret, as do others, his loss of this status and condition. By the time of his descent into Queen Vama's womb he has already attenuated his attachments to the world and his basic detachment is secure.

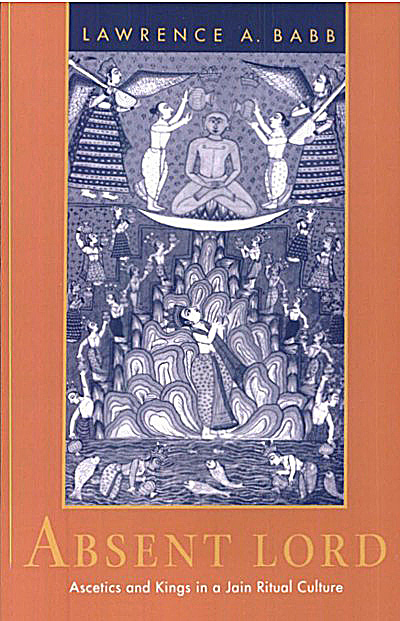

The fourteen dreams that precede his birth are emblematic of the parting of the two ways. As noted, the dreams can be interpreted as foretelling the birth either of a universal emperor or of a Tirthankar (Dundas 1992: 31-32; Jaini 1979: 7). A universal emperor embraces the entire world - one might even say devours it. The Tirthankar rejects it utterly; the potential conqueror of all thus becomes the renouncer of all. The rejection occurs with his initiation, and it is significant that before initiation he gives (as do all Tirthankars) gifts for a year - a dramatic and complete shedding of his wealth and of the world. Kingly largess and the ascetic's giving up are, at this moment, different aspects of the same thing. This idea is basic to Jain ritual culture, as we shall see. Then follow omniscience and the inception of his teaching mission. Unlike others who attain liberation, the Tirthankar, as the text tells us, is self-enlightened; he assists others on the road to liberation, but requires no assistance himself.

Having taught, he attains final liberation. His links with the world are severed entirely. Now, in completely isolated and omniscient bliss, he abides eternally in the abode of the liberated at the top of the universe.

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb

Prof. Dr. Lawrence A. Babb