15

Dance and Music in Jaina Literature

With special Reference to Kannada Literature

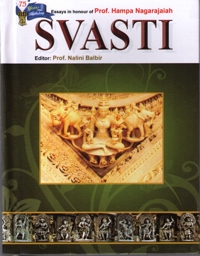

With deep respect and gratitude I offer this research article to SVASTI: Festschrift to Prof. Nagarajayya Hampa, the distinguished scholar in Jaina studies. It is an honour for me to contribute in this prestigious volume dedicated to him. It is our sincere wishes that his service to Kannada literature in general and to Jaina literature and culture in particular is going to be cherished through this publication.

Choodamani Nandagopal

Karnataka is fortunate to have writers of great merit and their detailed narration helps us to reconstruct Karnataka history and culture. Careful study of their literary works may bring out the techniques in the field of art and may help to differentiate the styles of those days from the present times in the art forms in particular dance and music. From early Chalukya to Vijayanagar times in every field of fine arts a number of literary works have been produced. The Jaina poets have contributed for the enrichment of Kannada literature. To embellish their narrative content they have amply used music, dance and other visual and performing art forms sensibly. By studying Kannada literature we draw authentic references to dance and music traditions which prevailed in respective centuries. The Kannada poets of repute are Pampa, Ranna, Ponna, Janna, Nāgavarma I, Nēmicandra, Nāgacandra II, Pārśvanātha, and Ratnākaravarṇi who contributed from 8th century to 17th century towards the development of Karnataka literature and arts.

The works of Pampa, top the list of literary references of all art forms. Arikesari II was the patron of Pampa. Pampa, the eight century Kannada poet is known as Ādikavi or the first poet of Kannada literature. He has written two major works namely, Ādipurāṇa and Vikramārjuna Vijaya. He had a thorough knowledge both in Sanskrit Kāvya and Nāṭyaśāstra. He studied all the earlier works such as Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, and the works of Kālidāsa, Bhāravi, Bāṇa, Māgha, Bhavabhūti, Harṣa and others. He was well versed in scriptures and art forms such as dance, music, painting and sculpture. It is a rare combination of all knowledge in a single person.[1] Pampa’s style of writing is delightful. Wherever the dance situation comes, with great enthusiasm and effect he narrates the dance sequence with all the technical terms used in Nāṭyaśāstra.

In his Ādipurāṇa there are situations where dance and music are described in detail, especially in two instances. The birth of Vṛṣabhadēva created great joy among the people on earth and gods in heaven. Indra shared the joy in organising the dance of Dēvāṅganas,the celestial nymphs. The celebration started from the dances of Dēvāṅganas.[2] They began the dance movements and picked up the rhythm by using 32 kinds of flowers. 32 dancers formed a design of flowers and petals in a circle and performed the movements which were a real feast to the eyes. Here the word ‘Citrapatra’ is used. There is a technique of dance known as ‘Citranāṭya’[3]which is now popular in the Kuchipudi classical dance style.

In the Dēvāṅgana dance number 32 types of flowers are spread on the ground. The colourful flowers form a beautiful colour picture. When the sequence of group dance reached its climax, Indra entered the platform and participated in the dance of the eternal bliss. Indra stood for the commencement of the dance in Viśākha Sthāna,[4] the position indicating horse riding or the use of weapons in the combat. He danced with Karaṇa (the unit of dance specified in Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata) and Aṅgahāras (specific number of karaṇas form an aṅgahāra). The term ‘Nāṭyarasam’ indicates the rasas or sentiments. The dance of joy of Indra synchronised with the Dēvāṅgana, the celestial music, navarasas, the nine sentiments and pādacāris, the intricate foot work. The Dēvāṅganas (celestial nymphs) joined Indra and formed a group sequence following the sentiments; emotions and rhythmic patterns, which were almost similar to the eternal dance of Indra, the principal deity of all gods.

The Eternal Dance of Nīlāñjana

Pampa takes up an opportunity in describing the dance style that existed in his times, by portraying the dance sequence of Nīlāñjana, a celestial dancer of Indra’s court.[5] This dance sequence is created purposely to divert the mind of Vṛṣabhadēva from worldly life. The dance of Nīlāñjana is the last such situation, which turns Vṛṣabhadēva into an ascetic who later becomes a Tīrthaṅkara and attains salvation. This is the turning point in the life of Vṛṣabhadēva. Pampa narrated very effectively this situation of realisation. This chapter is unique and gained greater importance because of his detailed narration on the dance of Nīlāñjana. Vṛṣabhadēva was fully absorbed and desired that Nīlāñjana’s dance should never end. She danced for such a long time that finally she was exhausted and dropped herself dead. Indra did not want Vṛṣabhadēva to experience rasabhaṅga, so he created another Nīlāñjana with his power and replaced her without anybody’s knowledge. Other spectators never realized the difference. But Vṛṣabhadēva, an expert in the art of dance and music, suddenly felt the difference, developed a great dejection towards life and left the place immediately. Nīlāñjana has shown all human emotions in her dance. The divine dance of Nīlāñjana is not only a glorious part of Ādipurāṇa but it is a unique and eternally memorable situation and the most charming episode in Kannada literature.[6]

The kings and gods assembled to witness the great dance organised by Indra. When he asked the assembly to select a subject, the assembly left the choice to the fancy of Indra. Here perhaps Pampa made his own choice and took up the dance pattern of his interest and pleasure. In the beginning he describes the physical form of Nīlāñjana and calls her as ‘Gaṇikātilakam’ (the central attraction of courtesans). Then he narrates the entrance of Nīlāñjana on the ‘Raṅga’ (Platform for dance). As the stage illumined slowly, she came out of the curtain, showing her face, as if a lightning emerged. Then she appeared before the audience performing “Puṣpāñjali”, scattering the flowers all around the stage and the court with rhythmic foot steps and lithesome movements.[7] The divine music followed with Tata (stringed instruments). Then came the Avanaddha (the instruments for rhythm such as Mṛdaṅga) instruments in first, second and third rhythm (Vilambita, Madhyama and Dhṛta laya) followed by the dancer’s foot steps. Then the melodious voice of a lady singer supported the divine dance of Nīlāñjana. Now the music and dance synchronised harmoniously to create an atmosphere of eternal bliss.

Nilanjana is a learned dancer and well versed in Bharataśāstra. Pampa used the word ‘Nāṭyagama’ to describe her. She employed all the 4 vṛttis:(the 4 styles of dancing) Bharati, Sātviki, Kaiśiki and Ārabhaṭi. Only an efficient dancer can perform all the 4 vṛttis. She performed navarasas, all the nine sentiments depicting the various stages in life with bhāva, vibhāva and anubhāva. She employed aptly the Sañcāri or the transitory status in dancing Abhinaya (the emotive form of dance).All the four folds of Abhinaya, Āṅgika (physical), Vācika (verbal), Āhārya (ornamental) and Sātvika (involuntary states of expression) were involved in her dance. The 32 Aṅgahāras and 108 Karaṇas were performed by her as in Bharatāgama (Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra). She kept a smiling face throughout her performance which is the pre-requisite for a dancer while performing before the audience.

The art, lyric, instrumental music, the dance, Nṛtya served as ornaments for her. All sentiments and emotions flowed deeply in her stature and posture. She was immersed in the melody and rhythm from head to toe, and every part of her body moved to the rasa she was depicting. Following rhythm, she expressed thousands of movements of pure dance. She reached such a height of climax in rhythm that the spectators became one with the dance of Nīlāñjana.

It appears as though Pampa must have experienced such a divine art. Perhaps royal courts of the Chalukya and Rastrakuta periods had such courtesans who were experts and deeply engrossed in their art. The history of Kannada literature reveals the remarkable influence of Pampa on later poets of Karnataka. Indeed the period of Kannada literature from Pampa to Basava that is 950-1116- A.D. has been justly named ‘The age of Pampa’.[8]

Ponna is another noted Kannada writer. His works also reflect the contemporary style in the field of fine arts. If Pampa is credited to be the first to introduce dance and music with great effect in literary works, Ponna is the promoter and successful narrator of the episodes where he, with great ease used dance and music sequences to embellish his literary power in his works. In Śāntipurāṇa (950 A.D.) Ponna has vividly described the dance of Apsaras[9] and Devendra.

The Apsaras exhibited the Sukumāra Nāṭya (lāsya) by using suitable Karaṇas and Aṅgahāras. In the tenth chapter Ponna describes the dance sequence of 32 dancers who under the direction of Indra formed a semicircle in the shape of a pearl necklace. They also designed by their feet various colour pictures with the help of flowers as described earlier by Pampa, the dance of 32 Apsaras i.e., Citrapatra Nāṭya. It appears that a dance pattern, performed by 32 members standing in different designs, drawing the colourful pictures stamping lightly on the flowers was very popular in the courts of Chalukyas and Rastrakutas. The same tradition in later periods came to be called as ‘Citra Nāṭya’. There are references to Citra Nāṭya in the Mysore School of dance. Bṛndāvana Nāṭya and Padmāvali Nāṭya are the other names used in this tradition.

As in Pampa’s Ādipurāṇa, Ponna also describes the Ānanda Nṛtya of Indra, the dance of ecstasy. Along with Puṣpāñjali, Indra took up the position of Vaiśākha Sthāna with great ease and started his dance in Āraḍhalī style (the virile expressions) with great devotion. Opposite to the Tāṇḍava thevirile style of Indra, the Sura-gaṇikas or the divine courtesans danced with great joy, the lāsya, thedelicateform of dance. Ponna had also greater experience of the pleasure of dance and musical art and he made use of this situation to express his love for art. His Śāntipurāṇa was so popular that queen Attimabbe got a thousand copies of Ponna’s Śāntipurāṇa copied and distributed.[10]

The patronage of art and literature continued in the times of Kalyana Chalukyans who ruled Karnataka from late 10th century to mid-13th century. The works in the field of art and literature received highest attention of the royals and commoners in this period. The rulers themselves were scholars of high caliber and wrote texts on music and dance. Nāgavarma I, Ranna, Udayāditya, Bilhaṇa, Vādirāja, Vijñaneśvara, Someśvara III, Pārśvadeva, Jagadekamalla II were great poets and also contributed greatly to the field of fine arts by adding passages of descriptions depicting the dual arts, dance and music.

Nāgavarma I (990 A.D.) was the court poet in the earlier days of Kalyana Chalukyas. His masterpiece Karnāṭaka Kādambari is the translation of Bāṇa’s Kādambarī. In the very beginning of the work, Nāgavarma writes about Mahasvete, an exponent in playing Vina. The divine melody of Vina echoed in the characterisation of Mahasvete and the presence of music felt in the narrative of the text.

Next to Nāgavarma I, Ranna (993 A.D.), the ornate poet of the royal court of Taila II followed the style of writing of Pampa. His patron bestowed him with the title Kavi Chakravarti, the emperor among poets. His work Paraśurāmacarita and Ajitapurāṇa have been highly placed in Kannada literature. An entire portion in the Ajitapurāṇa[11] written in 993 A.D. is dedicated to dance and music. Ranna has described in great detail the techniques and styles of dance practiced in his times. There are references of the terms and usages of the physical gesticulations, given by Bharata and also Nandikeśvara, the later writer who wrote Abhinaya Darpaṇa. It appears that by this time along with Nāṭyaśāstra, Nandikesvara’s Bharatārṇava and Abhinayadarpaṇa had gained importance and were considered equally popular on par with the Nāṭyaśāstra tradition. In this work(Chapter 5) Ranna has dedicated 37 verses purely for describing the dance of Indra. Indra dances Ānanda Tāṇḍava with 108 Karaṇas, 32 Aṅgahāras, suitable Recakas (hand and bodily movements)and Cāris (the specific limb movements).His dance was based on the fourfold Abhinayas or expression. The orchestra included Vina Vaṃśivādana or flute, talapranada, an instrument for rhythm (Tatāvanaddha ghana Suśira Vādya bhēda taraṅgal).

Ranna has also mentioned about Vicitra Nartana, variegated dancesof Vilāsinis (the courtesans). Indra and the beautiful maidens were completely absorbed in the dance from head to toe. In verse 21, Citra Nartana, the dance of drawing pictures is described in a vivid manner.

The description of the fascinating dance sequence in the words of Ranna unfolds in this manner: after completing the preliminary offerings, the actual dance numbers were introduced by Indra along with his associate dancers. The list of dance techniques as mentioned in Nāṭyaśāstra and other later texts are quoted authentically. The dance had Śṛṅgāra and navarasas, 8 Sthāyībhāvas (Permanent emotional states), 33 Sañcāri Bhāvas (emotions), four types of Abhinayas, Lokadharmi and Nāṭyadharmis (realistic school of expression according to the ways of the world). Nāṭyadharmi refers to theatrical expressions depending entirely on histrionic expressions adopted in four vṛttis: Bharati, Ārabhaṭi, Sātvaki and Kaiśiki. The four pravṛttis are Mānavati, Dākṣiṇātya, Pāñcāli and Mādra-Māgadhi.[12] Daiva Siddhi and Mānuṣa Siddhi are the two siddhis, the celestial and mortal achievements. The saptasvaras are Ṣaḍja, Riṣabha, Gāndhāra, Madhyama, Pancama Daivata and Niśāda. The Daśarūpakas mentioned are Nāṭakamam, Prakraṇamam, Benamum, Samavataramum, Dimamum, Ihāmṛgamaṃ, Vyāyogaṃ, Prahasanamum, and Ankamam Vithiyamemba Daśarūpa Lakṣanamam. Thus the dance of Indra presented the entire plethora of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra relating to dance and music.

Ranna gives further details: some dancers danced with complicated rhythmic patterns, others danced as though they were the rhythm themselves (Kelarutīgalē Tālamāgē kuṇidar kelabar). Ranna takes the opportunity to mention the different modes of laya, the times set to limited space such as Akṣasama, aṅgasama, tālasama, yatisama, lāsyasama, cānyasama, pādasama and paṇīsama. Then he gives a list of physical gesticulations such as 36 glances, the eye movements, 13 gestures of head, 7 gestures of eyebrows, 3 gestures of nose, 3 movements of lips, 3 movements of chin, 9 types of neck movements, 64 types of head movements (mastaka kriye),5 gestures of sides, 3 gestures of belly, 5 gestures of kaṭi. He also mentions Mārga, the classicaland Deśi, the regional, Tāṇḍava and Lāsya. Applying all the said techniques, Indra danced in ecstasy amidst the beautiful maidens, the celestial associate dancers.

The above description given by Ranna shows the depth of his knowledge in the Nāṭyaśāstra tradition of classical dance.Perhaps the contemporary dancers in the court of Kalyana Chalukyas performed the dance with utmost perfection. The artists of the period with dignity and maturity might have provided enough material for Ranna to give a detailed narration of art forms of that age.

Nemicandra, another Jaina poet, flourished in the court of Hoysala Ballala II. Nemiāthapurāṇa and Līlāvati are his important works. He has described the dance of Magadha Sundari in his Neminnāthapurāṇa (around 1190 A.D.). Magadha Sundari performed exquisitely the dance of Sama and Viṣama as expressed by Nemicandra.[13] The poet describes the dance techniques relating them to the various parts of the body of Sarasvatī, the Goddess of learning. The glances expressing emotions are attributed to the eyes of the goddess, the 108 Karaṇas to the ears, the 32 Aṅgahāras are like the pearl pendant, the Cāris are inevitable for the systematic dance, the Maṇḍalas are like the headdress for the goddess of learning, the various stances and gaits are suitably compared to the delicate form of Sarasvatī.

Nāgacandra II (1190 A.D.), a contemporary to Nemicandra, was also the court poet of Ballala II and was known as Abhinava Pampa. In his Mallināthapurāṇa he has codified the existing dance traditions in Karnataka. His descriptions when compared to the Hoysala sculptures reveal a new realm in the art forms of the Hoysala period. Nagachandra prescribes a tribhaṅga posture for Puṣpāñjali.[14] Nāgacandra uses the term aḍavus (various steps) while describing the dancer’s balance in her movements. In his lucid words he describes the way in which the dance movements, the rhythmic patterns on the drum and the melody of the song synchronised harmoniously. He mentions the regional dance traditions such as Goṇḍala and Vekkaṇa. Goṇḍala was a dance tradition which was very popular in Karnataka. It is described at length in Saṅgīta Ratnākara.[15]

There is one more depiction of Indra’s dance associated with the celebration of the birth of the Tīrthaṅkara Pārśvanātha. The poet Pārśvanātha during 1222 A.D. wrote the Pārśvanāthapurāṇa. In the 14th chapter of this work there is a detailed description of the dance of Indra. Pārśvanātha, like his predecessors made use of the situation to give an account of his knowledge in the field of dance and music.

Pārśvanātha also gives the entire list of dance techniques, as prescribed by Bharata in the Nāṭyaśāstra and as practiced in the 13th century.The fourfold classification of Abhinaya, and the emotive sentiments (Rasābhinaya) were performed with great ease. The Daśarūpakas were presented along with the gesticulation of Aṅgas and Pratyaṅgas (major and minor limbs) respectively.

The feet movements of the female dancers were so light and their graceful gait appeared like the gait of Swan. (Dēviyar pāda Vinyāsamam Haṃsī pāda Vinyāsamane pōltu).[16] This description gives an idea that the dancers adopted the tradition of Abhinayadarpaṇa also. These gaits are accessories to depict the bhāva, the sentiments in their movements and gesticulations.

Ratnākara Varṇi, an eminent Jaina poet belonging to Vijayanagar court has described the dance traditions that existed in Karnataka during the 16th century in the two chapters of Bharatēśa Vaibhava.[17] Ratnākara has elaborately described the dance techniques, which were very popular in the region of Karnataka. Ratnākara Varṇi captures our mind in lucid passages which are as remarkable for their graphic descriptions as for the accuracy of technical information.[18]

In the Pūrvanāṭaka Sandhi, RatnākaraVarṇi describes the dance of a courtesan who is a harlot (Beleveṇṇu) but highly efficient in the exposition of art. Ratnākara describes her physical charm and the erotic gestures she exhibited in the court of the king. Her eyes followed with emotions in the directions, whereas her hands moved in tremendous movements. She depicted with utmost ease the techniques of Bharataśāstra, such as 108 Karaṇas and 108 Sthānas (the finale position), 13 head movements, 64 varieties of hand gestures, 32 Cāris, 32 aṅgahāras, 36 rasadṛṣṭis with bhāva, and anubhāva expressions. Her movements were full of life. She appeared like a young snake moving in the sun with shimmering movements.

Her movements resounded in the Mardala (drum). While coming forward she resembled a wild wave with virile rhythm, while moving backward she was just like a delicate wave descending and becoming one with the great ocean. Her spinning movement reminded of the top when she took circular movements. In the middle of the stage (Raṅga) she danced with the gait of an intoxicated elephant (maddāne) and reached the high tempo and ended her recital in Ārabhaṭi (virile) natya. It appears the chief drummer was the chief vocalist for such a virile exposition.

Then Ratnakara narrates and gives a list of the group dances of his times in Uttaranāṭaka Sandhi. In the solo recital more attention was paid to the techniques, whereas in the group dances it is the arrangement of stage, symmetrical patterns and synchronisation of the movements of the dancers. The choreographic representation of dance is very well evidenced in the work of Ratnakara. In the first instance, the Haṃsamaṇḍalīnāṭya is an elaborate description of techniques, number of artists, and formation of patterns resembling a flower with sixteen petals, as if in a pond. There were 16 girls participating in this dance number, forming a single line in the gait of haṃsī (swan). Their tender movements of the feet bound by anklets resembled the voices of swans with their beaks, holding their hand gestures in mukulahasta.[19] Suddenly a dancer pretending anger on a male swan moves away from the group. But she returns to the pond and sits in the middle deeply engrossed in the thoughts of the male partner.

The other dancers, who had strong control over their limbs and feet, took leaps, not touching the ground and moved as if they were in the air, and slowly came down and with slight jump entered the pond with hand movements resembling a bird closing down the feathers. In the same delicate movements the dancers offered the flowers to the idol of Jina. The poet calls them as Kulavaniteyaru i.e. ladies coming from respectable families. While concluding the narration the poet imagines the spectators’ curiosity in witnessing other types of group dances such as Dikkannikānāṭya, Jalakannikānāṭya, Amarakāntanāṭya, Nāgakanyanṛtya, Bāṣpa-vidyullatānṛtya, Dyumaṇī Tāṇḍava, Candra Tāṇḍava Puṣpakanṛtya, Daśapadma-lāsya, Tārāṅgaṇānṛtya, Kalpalatānṛtya, Viṃśatipadmalāsya etc. It appears that all these are group compositions consisting of different numbers of dancers, depending on the type of composition they ought to present. Every piece had its own technique, unique postures and movements, woven around a theme. No doubt all these patterns were based on Piṇḍibandhas (group dance) of Bharatagulma, Śṛṅkhala and Latābandha formations. This shows the diversity in the group presentation of those days.

Further, Ratnākara Varṇi describes the folk and tribal dancers of his days namely Koravañjī, Jogināṭya and Koramanāṭya.[20] When the female dancers disguised as male tribes and danced it created a roar of laughter in the auditorium. Thus Ratnākara presented in his work the dance consisting of classical, regional and folk styles.

Aggala in his Candraprabha Purāṇaṃ describes the preliminaries as prescribed by Bharata. He also points out the balance and rhythm to be maintained by the drummer and the dancer. The synchronising effect of the drum and foot work creates the climax in the art of dance. Aggala also depicts the Tāṇḍava aspect of dance as “the surrounding trees swayed in ecstasy at the recaka movements of his feet, the quarter elephants supporting the earth and the heaven were struck dumb with the Parigha (iron bludgeon) of his arms, the earth trembled at the stamp of his feet and the ocean overflowed due to his swirling revolution.”[21]

Kamalabhava[22] (13th century) is another writer whose reference to the dance styles is worth mentioning. The preliminaries are also described by him by giving the details of the orchestra set to play on the instruments with the dance director who was to perform the rite of Puṣpāñjali. The Kutapa (orchestra) included the drone keepers, singers, four different flutists, the players of Vinas and the cymbal players. He calls them as vividha vicitra vādana viśāradaru.

Kamalabhava while describing dance sequences gives a detailed list of dance techniques performed by the dancers in the marga tradition (classical) such as 13 types of head movements, 24 single handed, 13 combined handed gestures, 108 Karaṇas, 32 cāris, 32 aṅgahāras, 8 rasa dṛṣṭis, 8 bhāva dṛṣṭis, 20 sancāri dṛṣṭis, 9 eyeball movements, 8 looks, including 9 of sides, 7 of eyebrows, 6 of the nose, 6 of the lips, 7 of the jaw, 9 of the neck, 5 of the thighs, 5 of the hips, 9 standing postures, 12 gaits, 6 graceful postures, 4 facial moods etc.

Bāhubali (1690 A.D.) is another very important contributor as far as the references of dance sequences are concerned. In his Nāgakumāracaritaṃ he depicts vividly the dress and ornamentation of a dancer and the musical band. He gives a pure Karnataka tradition of the sequence. After Puṣpāñjali the dance was continued to songs in the Sulādi tālas, followed by nāganāṭya, Varalakṣmi and bhoga nāṭya.[23] At the time of Bāhubali it appears that Sulādi tāla[24] a musical composition was very well adopted in the dance recitals also. The singing and dancing of this composition demands great skill in the manipulation of time measures. Bahubali gives the information that the dance recital concluded by Kaivāda Prabandha, which more or less corresponds to the modern tillāna of Karnataka music. Govinda Vaidya (1684 A.D.) in Kaṇṭhīrava Narasarāja Vijayaṃ describes other dances such as kola, birudina nāṭya, prabandha, jati, jakkini, rājaka,

The literary works in Kannada ranging from the time of Pampa (940 A.D.) to the times of Bāhubali (1690 A.D.) provide a rich source for studying the dance and music traditions that prevailed in Karnataka. If the Mārga style (classical) was deep rooted in the dance systems, it has also given a wide scope for regional developments in the field of dance. One should be grateful to the writers for mentioning and describing the deśi (regional) traditions practiced in Karnataka. The present dance system in Karnataka is very much different from the past, as it has received impact from the styles of Tamilnadu and Andhra. The resurrection and reconstruction of the dance tradition of Karnataka can be justly done by a careful study of all the techniques that these Kannada authors have described in great detail.So far we have examined the various Kannada works which have a bearing on dance and music in Karnataka. There are some Sanskrit works written in Karnataka which also describe in detail dance and music as practised in their times. However, it has to be noted that most of them are essentially based upon Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra.

The survey of literary works from early times to the Vijayanagar period has provided a theoretical background of dance form that existed in Karnataka. The texts on music and dance were compiled and even today they are regarded as the source for reconstructing the traditions of dance and music in Karnataka. The detailed study of these texts and adoption of forms discussed therein would bring a new life to the existing system of Bharatanatyam. These Jaina literary works in Kannada have nourished the tradition of music and dance and therein set the chronology in the evolution and development of Karnataka dance and music. They also show that the tradition was not static but dynamic and absorbed influences and new elements that arose at various periods because of a variety of reasons. Thus these literary works have an important place in the study of Indian music and dance.

References

Ādipurāṇa of Pampa, ed. Kundanagar K.G and Changale A.P, Belgaum 1953.

R.r. Divakar (ed.), Karnataka Through the Ages, Mysore 1968.

Kamlabhava, Śāntīśvara Purāṇa, ed.Ramanuja Iyengar Mysore 1912.

D.L. Narasimhachar, Karnāṭaka Darśana, Mysore 1904.

Nemicandra - Nēminātha Purāṇa, ed. Ramanuja Iyengar, Mysore 1914.

Ponna, Śāntipurāṇa, ed. Venkata Rao, A.shesha Iyengar, Madras 1925.

Ranna, Ajitanātha Purāṇa, ed. Ramanuja Iyengar Mysore 1910.

Ratnākara Varṇi - Bharatēśa Vaibhava, Ed. Mangesa Rao Mangalore 1923.

R. Satyanarayana, Dance traditions of Karnataka, Studies in Indian Dance,Mysore 1968.

V. Seetaramayya, Mahākavi Pampa, Mysore 1975.

Kuchipudi is the dance style of Andhra Pradesh. One of the dance techniques is known as ‘Citra Nāṭya’ giving popularity among present dancers. The colour powder is spread on the ground; a white cloth is spread on the colour, the dancer with her feet according to rhythm and timings moves on the cloth. After the completion of rhythmic note when the cloth rose from the ground a design is printed on it. Usually they draw seated Vinayaka, peacock, lion (Simha vahini).

Vaiśākha sthāna - 3 types of position prescribed for men keeping 3-½ tala distance between feet and keeping the thighs at the same distance and sitting half on the feet.

Puṣāñjali - Even today the Bharatanatyam dancers enter the stage with flowers in their hands and scatter them on the stage and bow to the God and musicians and then start their dance.

Ajitanāthapurāṇa of Ranna, Ch. 5.

Line 19: Virājisitu hastapāda vinyāsaṃ kulisiya tōlaṅgalaṃ sam |

Saṃsthaladol karatāladoleseva maṇibandhadalaṅguliyaṃ nakhadol nartana vilāsamaṃ meredarindra saundariahal ||

Pravrthi: This is the regional identity recognised through costumes, dialects, habit, tradition, custom and occupation. They vary from one region to another. Bharata has classified four identities such as Mānavati orWestern, Dākṣiṇātya or Southern, Pāñcāli or Eastern, and Māgadha Māgadhī or Northern regions of India.

Nemināthapurāṇa by Nemicandra, Ch. III Dance of Magadha sundari.

Antu sama viśamavembaradum tereda nāṭyamatyanta manōharaṃ kauṭika karamumāge |

Nandikeśvara has given a list of gaits - 10 types Haṃsī, Mayūri, Māgi, Gajagali, Turaṅgiṇi, Siṃhī, Bhujaṅgi, Maṇḍuki, Vīra and Mānavi.

Bharateśa Vaibhava byRatnākara Varṇi, Ch. Bhōga Vijaya - Pūrva Nāṭaka Sandhi and Uttara Nāṭaka Sandhi.

Mukulahasta - Here the use of this gesture representing the beak of a bird is exactly as in Sārasaṅgraha. But this use is not mentioned in the Nāṭyaśāstra.

Sripadaraya in 1500 A.D. composed many Sulādis and Purandaradasa followed the technique of the Suladi tala of Sripadaraya. Five or seven of the Sulādi tālas are used in the pallavi and caraṇas and at the end of the composition there are two lines called Jale (couplets) which have to be sung in all the five or seven tālas used for pallavi and caraṇa.

Dr. Choodamani Nandagopal

Dr. Choodamani Nandagopal